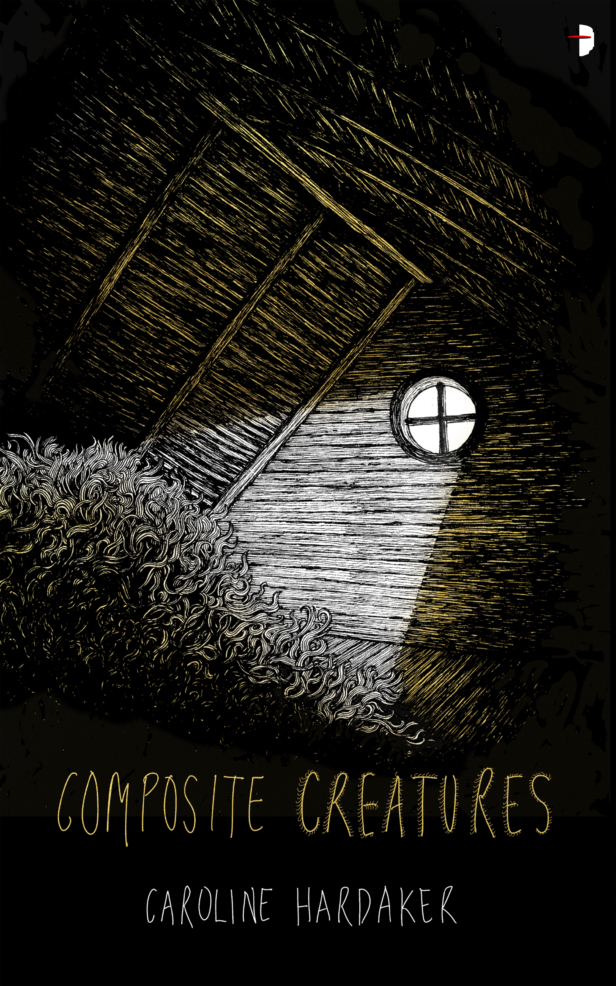

We are delighted to be able to reveal the wonderful cover of Composite Creatures by published poet and first-time novelist Caroline Hardaker.

Set in a society where self-preservation is as much an art as a science, Composite Creatures follows Norah and Arthur, who are learning how to co-exist in their new little world. Though they hardly know each other, everything seems to be going perfectly – from the home they’re building together to the ring on Norah’s finger.

But survival in this world is a tricky thing, the air is thicker every day and illness creeps fast through the body. And the earth is becoming increasingly hostile to live in. Fortunately, Easton Grove is here for that in the form of a perfect little bundle to take home and harvest. You can live for as long as you keep it – or her – close.

Not enough to get you excited for Composite Creatures? Okay, here’s the first chapter of the book, enjoy!

There are some things I remember perfectly. I can close my eyes and be there; in school, shaping a stegosaurus with playdough, climbing stone walls and wooden stiles with Mum, or even on the observatory roof, hand-in-hand with Luke, searching through the smog for sparks of life. Even now, I see his face lit green beneath the moon, smiling in absolute awe at the cosmos and proving without doubt that he had eyes only for antiquities. The way things were. The stars were so bright that I could hear them, like glass shattering. They’ve never shone so brilliantly since.

But the fact I can relive all these things so vividly just convinces me that I’ve made them all up. Each time I play these memories through, Mum or Luke say something new. It’s always something that warms my belly, something that makes me feel better. Only occasionally is it something that hits me hard. But even then, it still strikes a low satisfying note telling me I was right about being wrong, all along. What would you call that?

I wonder if it matters, whether these images are real. It’s somewhere to go that’s dark and balmy. We all do it, don’t we? Where do you go?

A long time ago, Mum told me that in her youth the sky would flock in spring and autumn with migrating starlings, finches, even gulls. Huge grey and white beacons of the sea. I’ve heard recordings of their calls – somewhere between a lighthouse’s horn and a baby’s wail. I sometimes close my eyes and imagine how it would sound as hundreds of gulls moved across the blue like shot-spray, all wailing to each other out of sync. Ghosts that swam the sky. I think it would sound like the end of the world.

Over the years, Mum had collected all the fallen feathers she’d found in the garden, on the roof, in the gutter. There was nowhere too low for her to stoop, no mud too deep or sticky for her to squish her knees into and scoop out the treasure. She rinsed the feathers as best she could and balanced them in egg-cups wedged between books on shelves. “Stuff of stories now,” she’d murmur as she pointed them out to me one after another, telling me which birds they came from. This one a barn owl. This one a crow. But she might have well been naming dinosaurs – I couldn’t picture any of them. All the illustrations in Mum’s reference books were completely flat. One time, we were sitting on the garden wall together when a bird landed on a perch above us and made the strangest sound, sort of a low whistle. I’d never seen anything like it, with its fat grey form and striped underbelly, but Mum just laughed at it and clasped my face between her hands. “Are we supposed to think that’s a cuckoo? The little patchwork prince. You can almost hear the clockwork.” I felt silly then and didn’t look back up at the cuckoo, but I kept listening for a tell-tale ticking that never came. Perhaps Mum could hear something I couldn’t.

Still, I continued to stroke Mum’s collection of genuine feathers, gliding the silky fronds between my fingers. Something about them always made me want to pull away, but Mum encouraged me to keep going, to know what they feel like. But it was confusing for me. Was the feather still alive, like the bird had been? I wanted to stick their sharp shafts into the skin on the back of my hands and wave them in the wind. “Be gentle, Norah,” she’d whisper, “They’re fragile, and who knows if we’ll find more.”

I wished I could see inside her head. I could almost feel them, her thoughts, or at least the shape of them. She was my Mum. But the things she said, the things she lifted from mysterious drawers – they were from another world. She looked up to the sky for things I couldn’t understand, always through her old binoculars; heavy black things, held into shape by stitched skins. She liked to shock me with little facts, things like, “When I was little, the sky was full of diamonds that you could only see at night,” and “Me and your Gran used to lie on our backs and watch fluffy clouds go by. You could see shapes in them, and if you asked the sky a question, it sometimes told you the future. The more stories she told, the less I believed her, and sometimes gently pushed my hands in her belly, saying, “You’re fibbing, tell the truth,” but she’d just shake her head so her red curls bounced over her face and promised that it was the truth, she’d seen it with her own eyes. One night, she even told me that “The moon was as white as a pearl.” At the time, I didn’t know what a pearl was, which seemed to make her sadder. She pulled me to her side and pressed the binoculars to my face. “Keep looking, Norah – the birds – they might come back. They might.”

I don’t know if I believed that. The birds had just stopped, it was their choice. There was always a muddle of reasons for it over the years; climate change, lack of habitats, a faltering ecosystem. The fact that the earth and sky are turning plastic. I remember when I was little, seeing on TV the reports about initiatives to encourage the building of bird boxes and custom annexes on business premises. Children’s TV shows had segments where the hosts showed you how to build your own bug-hotel or bird-feeder out of an old pine cone, but I didn’t know anyone who managed to actually bring anything to roost. Later, after I’d discovered the joy of watching the world through Mum’s binoculars, I did ask her when it’d all started, the fading away of wildlife in the sky and soil. But she just looked out of the window and squinted her eyes against the white-grey sky. “It all happened so gradually,” she said. “I don’t think any of us noticed until they’d gone.”

Mum tried to make me believe the miraculous could happen, that surprises were around every corner. But even then, I only nodded and smiled to be nice, to make her feel better. I’ve never understood why people need to believe in something we can’t see. It’s like reality isn’t enough – they constantly need wonder, awe. When Art and I were dating, even in the earliest days, he always threw in the unexpected. For our very first date, we arranged to go for a meal at a French restaurant, La Folie. I spent far too long tangling myself up in dozens of outfits before deciding on a pair of rose-gold trousers and a black chiffon shirt, only a bit sheer.

At thirty-one, I wondered if I was a bit too old for clothes that showed so much of me, or whether I’d come across as desperate. I ran my hands over the shape of me, repeating to myself the mantra; “I do look good, I do look good.” Even after I’d committed to an outfit, I couldn’t stop faffing. I tried the shirt my usual way of leaving it loose and flowing, but it just didn’t seem right. I then tried tucking it in but I couldn’t stand feeling constrained. In the end I undid the last three buttons and tied the open panels in a bow. Already the chiffon was sticking to my skin. My hair – a fluffy brown nightmare at the best of times – was unusually coy and submitted to being clipped to the side with a gold triangle pin. I painted my skin in bronze and peach, finishing myself as I would a precious gift. When I caught my reflection in the mirror I hardly recognised myself, and fought the instinct to wipe it all away. Maybe it was good that I felt like a stranger. This was the new me – a new beginning. Perhaps a costume was what I needed.

I took a taxi straight to the restaurant, my cheeks burning all the way at how late I was. At one point I lowered the window to cool myself down and the caustic city air stung my nostrils. It was so much worse in this area of the city. How could I forget to wear perfume? Stupid. All I could hope was that the restaurant had plenty of scented candles and a top-notch purifier. I rolled the window back up and tried fanning my face with my handbag, but a quick glance at my watch and I was distracted again. First impressions are so important. Though in the end, my lateness probably wasn’t a bad thing – my desperation to get there quickly proved to be the perfect distraction from my beating heart, the mounting sense of panic rising up my throat.

I flew into the restaurant not at all thinking about how I looked or whether the other diners would guess why I was there. I spotted Art straight away, sitting at a table in the far corner of the restaurant, a leather portfolio resting between the cutlery in front of him as if he was ready to eat it. The bronze ankh and ‘E.G.’ stamped on the cover shone in the candlelight.

I weaved my way between tables crushed with friends and lovers all leaning towards each other, all baring their teeth and spilling wine, and finally reached our table. Art stood up when he saw me coming, the fingers of his right hand twitching a little, his right arm pinned down by his left.

“I’m so sorry, Arthur –”

He stopped me short by pulling me into an embrace.

“Don’t worry about it, you look beautiful.”

My arms wrapped around his shoulders, bending on wooden hinges and dangling on strings. I was conscious that I stood a little taller than him, and my elbows awkwardly sought out the place they would have sat before, which now was empty space. I finally let my arms rest on his shoulder blades, acutely aware of how the expanse of my hands fanned across his back.

We sat, and I saw there was already a glass of red wine waiting for me. I picked up the glass by the stem and took a sip, my tongue shrinking away from its dry and mossy texture. Art picked up his glass and took a long, romantic draft, his eyes on my eyes on his eyes. His hair was cropped much shorter than when I’d watched him in the waiting room. Then, he’d had an early hint of a beard too, but now his skin was shaved so close that his cheeks and chin looked like porcelain. I wondered whether he would break, if I touched him. Would everything break? As soon as I sat down, he grabbed my hand and gave it a squeeze. His palm was dry and rubbery, not like china at all.

No, it wouldn’t break. I’d make sure of it.

But then the worst happened. Within minutes of me getting there, I didn’t have anything to say. My tongue rolled in my empty mouth searching for something, anything to fill in this enormous chasm before it got even wider. But I’d stalled, utterly and completely. Art’s eyes were huge and exposing, and all I could think about was how his skin was even paler than mine, how his hair would feel between my fingers. Bristly, maybe. Not soft. It could’ve been seconds, it could’ve been minutes – but it felt like years were spinning by and I couldn’t get off the carousel.

Art smiled, showing rows of straight, white teeth with a little gap between the front two around the size of a penny’s cross-section. “I thought this might happen.” He reached below his chair and on sitting up swung his arm in a flamboyant arc up to the ceiling before bringing down on his head a miniature yellow party hat shaped like an ice cream cone, peaked with a cloud of fluorescent pom-poms. “Happy first date day!” he sang, his arms stretching wide in celebration. I laughed, spitting puce across the table and then covering my face with my hands, as if denying I had a mouth at all. He pulled a second hat from beneath his seat, this time shaped like a canoe with long strings dangling from the front and back like a horse’s tail. He thrust it towards me. “I thought it might break the tension. Join me?”

Terrified, I took it by the tassel and didn’t know what to do. Wasn’t everyone in the restaurant already looking?

“I–”

“Come on, put it on!”

In the end, I did it not because I wanted to, but because I thought it might showcase us as a real couple, celebrating a birthday, or anniversary. The other diners would whisper, “Well, they must know each other already. Why else would they dare to be so ostentatious?” I grinned back at Art as if it was all for him, only letting a hint of self-consciousness shine though. And you know what? As soon as I pulled the hat over my eyes, something changed. I couldn’t even see if anyone was looking anymore, and that slight act of outrageousness overshadowed mine and Art’s feeble history. Now, we were set apart from everyone else in a positive way. We were the loud ones, the ones everyone deliberately tried to ignore. It was genius. We had our first funny story. “Remember the hats, darling? Tell them about the hats!”

Art moved his portfolio aside to the edge of the table, leaving it closed, and I didn’t even take mine out of my bag. The whole thing felt surprisingly organic, and we moved through the night at the same pace, holding hands through time. He told me a little about his family in Wisconsin, how he’d moved to New York in his early twenties to get away from the crowd he left behind. He was vague about the details, and when I asked him about it he just shook his head and took a drink. It wasn’t that he avoided it, but I picked up that he saw his life in the US as a chapter which had very much ended. At this point he’d only been living in the UK for a few months, but it sounded like he was determined to cut ties with everyone back home. He said it was “Simpler”. So, I was going to be taking on Arthur alone, no extra baggage, which pleased me. Nice and clean.

I watched him all the time. While he talked, he had an odd little tic of pulling on the fleshy bit of his ear as he tied-off sentences, and he often looked at me sideways when I talked for more than a couple of sentences. When he ate, he never touched the cutlery with his lips or teeth, and simply dropped the food into his mouth. He opened his eyes particularly widely when listening, as if he heard more with the whites.

Our little table was positioned in front of a huge aquarium, which reached up to the ceiling and across the wall. The glass looked thick as brick, and made a dull ‘clunk’ when Art tapped a knuckle on it. At head height, between the waving reeds, a shoal of guppies flickered with long, flashy tails, and fish with dalmatians’ spots cut through the gloom to follow my finger across the glass. We each picked our favourite fish. Art chose a white guppy with a blue sheen which he named Albatross, and I chose the little brown catfish, which snuffled around on the sand with her feline whiskers and otter-like mouth. She was the only one that moved slowly enough for me to make out the tiny stitches holding her together, the bulging seams.

The right time never came to show our portfolios, so we decided to exchange them at the end of the night, taking them home to read before discussing them at our next date. I was even more thrilled about this than I let on, as this seemed like a far less mortifying way to share the inevitable. If only we all could be absent when we’re standing in the centre of someone else’s room for the first time, naked.

Surprisingly, deciding what to include in my portfolio hadn’t been as difficult as working out what to wear that night. Easton Grove had sent me their official protocol list, but I didn’t need it. I seemed to just know what would be required of me, and putting this on paper was always easier than living it in the flesh.

I included my CV, which mainly recorded my career history beginning with my teenage job in the bakery and ending with my insurance job at Stokers. I tried to make the most of my responsibilities, keen to make myself seem like a ‘catch’, but it was obvious to anyone reading the facts that I was more of a ‘cog’. Once I realised that, it seemed better to be frank about it upfront after all. My job was to process small insurance claims. I never spoke to the clients myself – my part was to sit in the middle and transform loss into bankable assets – but I sometimes watched their appointments with the suits and ties through the glass walls of the meeting room. Basically, I saw everyone’s misfortunes, and turned the gears enough for a few pennies to come out somewhere down the line. Though how much dropped into their purse, whenever it did, was never enough. Their eyes said it, even if their lips didn’t.

On its own though, my career history seemed pitiful, so I also included a photograph of the house I grew up on the Northumberland coast – the rows of houses behind all painted in their pastel colours, prints of two of Mum’s paintings (one of me sitting at a little table with a book and the other of a sea, split by the leap of a blue whale), and a USB stick, containing a file of Edith Piaf songs. I had ummed and ahhed about the music, something about it seemed a bit – pretentious. But I knew the rise and fall of the melodies by heart, and though I didn’t know what the lyrics meant it didn’t matter, because the notes made my blood flow in quixotic waves. I hope Art would understand that, even just a little bit.

This all would’ve been fine on its own, but my portfolio still lacked the spark that made me, me. This disturbed me, because the gaps say more about you than what’s between the pages. I tried writing something, a poem, a few lines of meaning, but it went nowhere and meant nothing. So after a few increasingly frustrated evenings of scribbling, I scrapped my futile attempt at creativity and instead slipped inside an old photo of a seagull that I’d picked up at an antiques market years before. I wished I still had the feathers in the egg-cups. How significant it would have been to fold something so irrefutable between my pages. But they were all gone now.

By the time I got home from La Folie, the shiraz was bubbling back up my throat. I locked the door to my flat and threw myself on the sofa, face-down. The room shuddered and swayed, the walls pulsing with the beat of Art’s voice, every word he’d spoken. It was late and my flat was silent, yet it was so very, very loud.

I turned on the TV to drown it out, and unzipped Art’s leather folio on the coffee table. He’d included his CV, ironed crisp, detailing his journey from his first job as a junior copywriter to full-time authorship. Here was a list of his published novels, and I counted seventeen, including the one currently in progress. Scanning the list, I hadn’t read any of them, but I’d heard of one or two of the titles, and could remember one or two of the covers. They were all crime novels, not my sort of thing but the sort of paperback people snap up at the airport for holiday reading. I would never have told him this, but I looked down on them. These were lives written to templates, and it made my skin crawl that the main character – though so flawed in all the usual ways – claimed to never see the ending coming.

But looking at Art’s list of successes was still enviable, and with a sickening jolt I realised that he would be looking at my own paltry resumé right now. I let the CV waft back onto the table and picked up one of the two novels he’d included. The title ‘Frame of Impact’ groaned in heavy blue and black. I turned it over and on the back was a black and white picture of Art sitting in a library, the desk in front of him messy with open volumes and stacks of old hardbacks, as if playing a detective himself. He didn’t look like the Art in the party hat. This was Arthur McIntyre, who didn’t laugh or smile. His eyes were smaller, concealed behind thick-framed acetate glasses that he might’ve found in a fancy-dress shop.

There was a photo in the folder too; Art when he couldn’t have been more than five or six, standing beside a couple wearing the protective green overalls, wide-brimmed hats, and veils of the scatterers. Behind them stood a row of sealed white tents and chemical sprinklers pipes. Above the awnings and half out of shot, I could just about make out the edge of an iron cage suspended in mid-air – a tractor, or harvester of some sort. Through the mesh, the woman grinned from ear to ear with the same straight and square teeth Art had. The same wide, white eyes, but set into a face that had lost a lot of weight. Skin hung loose beneath her chin, her neck a slim column of blue tendons. The man, who must have been Art’s dad, stood head and shoulders above the woman, and wore a sharp grimace. One arm pinned the woman close to him, while the other held Art’s wrist. Art was half-standing and half-sitting, as if his legs had buckled and the photographer had captured the exact moment he’d started to fall. He was looking away to the right, at something beyond the edge of the snapshot, with his mouth gaping, his eyes angry and small. I propped the photo up against a cup on the coffee table.

Back to the folder. Next up was a pile of letters, folded carefully into envelopes which were badly crinkled at the corners. I knew what these were. Art had been telling me about a pen-pal he’d had in his early teens who lived in England, a girl the same age named Wendy. They’d been matched up by a school programme and written to each other for four years, comparing their day-to-day lives and sharing ambitions that transfigured with every letter. They never met in person. Art said that as the years went by he’d get a thrill when a new letter arrived in his mailbox, and he’d rush straight upstairs to his bedroom to read Wendy’s news. But when it came to writing back he’d hit a blank, and end up repeating the same stories, hating himself for his laziness and the banality of what his life must sound like. So he started to make things up, but when he received further replies from Wendy he was surprised to see she wasn’t as captivated as he’d imagined she’d be. She just wrote about herself.

His stories became more and more elaborate and unrealistic, until he ended up writing stories for himself, rather than Wendy. This way, he could live a thousand different lives without lying to anyone. He kept Wendy’s letters, and when the opportunity came (years later) to move to the UK he snapped up the chance, this being the only other home he felt he knew.

The final piece of himself Art had included in the folio were a pair of purple socks, spotted with red. They were obviously well worn, the heels thin and threadbare. When the voices began to settle and I could raise my head again, I carried the socks to my bedroom, closed my eyes, and threw them towards the bed. They lay at the foot on the right hand side. I stared at them for some time before stripping and crawling under the covers on the left side, trying to forget that the socks were new and convincing myself that having them there was utterly, utterly normal.

Composite Creatures is set for release on 13 April 2021 from Angry Robot.