Writing historical fantasy should be easy. After all, if you’re going to put gods, monsters, devils, demons, witches or even the odd unicorn into, say, the US invasion of Grenada in 1983, then getting the exact deployment of the enemy communist forces (I always struggle to remember if it was two fishing boats and a windsurfer vs the 82nd Airborne or two windsurfers and a fishing boat) can seem unimportant.

However, it isn’t. One of the bonuses a writer gets from using a real historical period is an added sense of realism. One of the problems is that some of your readers may be experts on the period involved and, while they’re quite prepared to accept that Lincoln’s assassin was working under the enchantment of white supremacist wizards, they will not forgive you for getting wrong the name of the band he was watching when he died, nor for mistaking the sort of bomb used. (Only joking about the band. And the bomb.)

But this isn’t the only reason you might want to consider sticking as close as possible to historical fact for the non-fantastic elements of your story. History is very often more incredible than anything dreamed up in fantasy literature. Anyone who has read the life of Edward III, for instance, would struggle to believe that a 16-year-old boy could direct a handful of men through a secret passage in a castle, avoiding 200 defenders, to abduct and kill the man who had usurped his power. Getting the details just right can add to a story’s sense of authenticity and spark other ideas in a writer’s mind – why isn’t that passage there today?

To me, it’s very important that when you come to designing the fantastic elements of your story you root them deeply in the historical period in which you are writing. If you’re just going to whack a random monster into a story it won’t have the same clout unless you think very carefully about the beliefs and superstitions of the day and let the story emerge from them.

My trick is usually the same in whatever period I’m writing. I take those beliefs and superstitions and treat them as if they were fact. So, when I write in the 100 Years War, kings are really appointed by God and can talk to angels. God really wants the poor to remain poor – he sets an immutable social order. So who do the poor turn to if they want to change that? When I write in the Viking age or continue that story on to more modern times, Gods do walk the earth, talk with people, runes do contain power, men can become wolves. Loki might be seen as the bad guy to the gods but, in the sagas, he helps ordinary people. He’s also virtually the only major Norse god who isn’t some sort of god of war. What are the implications of that?

Of course, for dramatic effect you can play with history and conflate things, move events in time or space. Having said that, it’s probably better not to follow romance writer Barbara Cartland, who when cowriting with war hero Louis Mountbatten, suggested moving the Battle of Trafalgar to the Caribbean so she could have some colourful pirates in it.

One of my favourite series at the moment is Vikings and it shows very well how to write historical fantasy – for that’s what it is, with its wandering gods and its sorcerers. It also shows some of the pitfalls.

Generally the show does very well. The opening season in particular is full of lovely little details that warm the heart of anyone who knows the period. The make up for men, the complete lack of embarrassment about sex, the isolated farms, the massive leap forward in technology represented by the longship that triggered the Viking age, the sense that all things are destined and that people have next to no say in their own fates, the impact Christianity had on the Norsemen and, even more so, the impact that Christians themselves had. Monks could write, which brought about a whole new social system of control over kingdoms for those kings who could employ them.

I also loved Lagertha defending the homestead. There’s a lot of debate about Shield Maidens in the Viking period – fierce female warriors – and recent excavations suggests that they may have been more than myth. Whatever the truth of women actually taking part in warrior culture, it’s surely true that, with men away on ships, women would have had to defend against opportunistic raiders and also that, when travelling to strange lands, men, women and children would have had to defend against attacks. The relative sexual equality between men and women depicted in the show is also accurate and women had the right of divorce. The cadre of female warriors that appears later? Who knows?

The show draws heavily on the Viking sagas, usually in a fairly accurate way.

Ragnar was really captured by Aella of Northumbria and thrown into a pit of snakes, the sagas say. He really was avenged by The Great Heathen Army, led by Ivar the Boneless, though it’s not known why Ivar was called ‘Boneless’. The writers of Vikings did a superb job of imagining how these events might have been propelled by the characters involved in them. I think this is the key to good historical fantasy and the key to all good drama – the characters drive the events, not the events, the characters, no matter what the historical reality may have been.

Of course, there are things in the series to annoy the nitpicker. The interiors of the longhouses are, as far as my research reveals, much more high medieval period than 8th century. They are rather over furnished by Viking standards.

The stirrups and saddles look anachronistic to me – yes, I notice stirrups. I would thrill to see a real Viking turf saddle, not a modern-ish leather job. I might have dreamed that Ivar had a wheelchair made for him. I hope I did. Still, we can live with all this – just as the siege engines deployed in an open battle didn’t much spoil Gladiator for me, nor the fact that the fire arrow seems the weapon of choice for any ancient world or medieval battle that ever appears on TV.

However, there are points at which Vikings’ departure from history grated on me – as someone who has read a lot in the Viking period. My wife gets sick of me shouting ‘no!’ at the TV every time anyone goes to consult with the seer. I think it annoys me so much because a lot of the religious side of the series is done very well and clearly comes from descriptions in the Viking sagas. However, the depiction of male sorcerers and seers is, as far as my reading reveals, a serious blunder.

To the Vikings, magic was a woman’s realm. The culture’s most famous poem – the Voluspa – means ‘Prophecy of the Seeress’ and concerns the beginning and end of the world, or at least the end of the time of the gods. The magic symbol of the Viking sorcerers was the distaff – the woman’s spinning implement – and there have been 40 excavations of graves in which recognisable wands have been buried with women. The Volva or Vala (seers) practised Seid (magic) and were highly respected. Vikings hero Ragnar would have certainly been glad to consult with a witch. However, if he had come across a male sorcerer, of the sort depicted in the series, his reaction would have been very different. The Viking king Harald Fairhair had a son who practised magic. The king had him burned to death in a house, along with several others he accused as sorcerers. Magic was seen as effeminate and, while it’s very difficult to call the Vikings anything as modern as homophobic, they certainly had a strong idea of what a man’s role was and what a woman’s. Magic was strictly female.

I think the writers missed a trick here – there would be a whole plotline to be had out of the Viking attitudes to magic, particularly its links to sex, which were strong. It might have been interesting to see one of Ragnar’s sons turn to magic and to see Ragnar’s reaction to it. They could have taken the mythology of the day and treated it as true, and seen what consequences that had. Instead, the seer in his little hut just seems like a bit of an appendage, something stuck on – which essentially he is.

That said, the series is altogether pretty good and uses its source material well. Personally, I’m looking forward to the appearance of Harald Hardrada – mercenary, warrior, pirate, legend. I think we’re bound to see him. And, of course, the development of Alfred the Great. The fantastical elements of the series have somewhat faded in later seasons. It would be good to see them return and to see what these historical figures make of them.

That’s the fun of writing historical fantasy, of jumping off at one point and seeing it all the way through, watching the little change you have made cascade through history. There you make new worlds, as fascinating as anything produced by straight fantasy or SF.

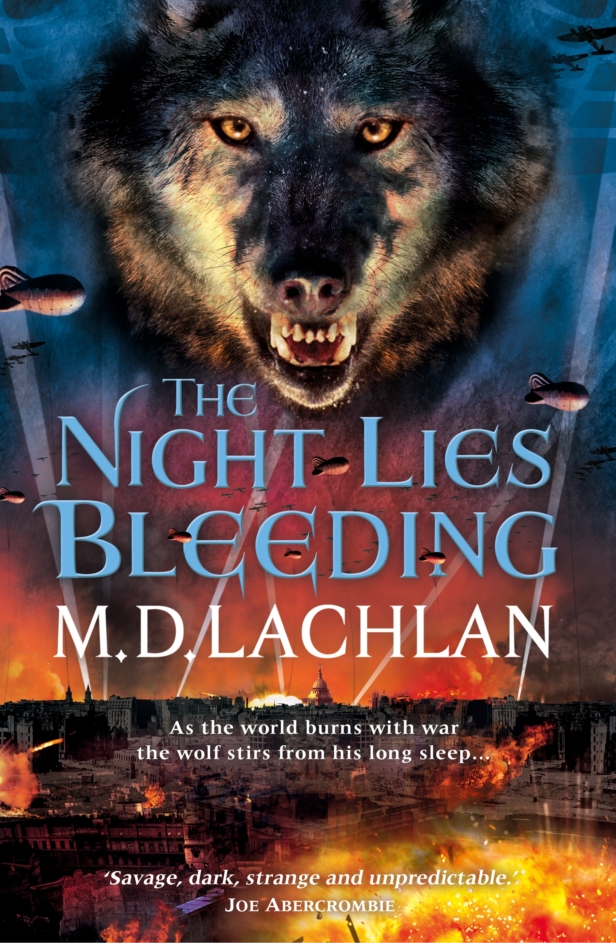

MD Lachlan’s latest historical fantasy, The Night Lies Bleeding, is out now from Gollancz.