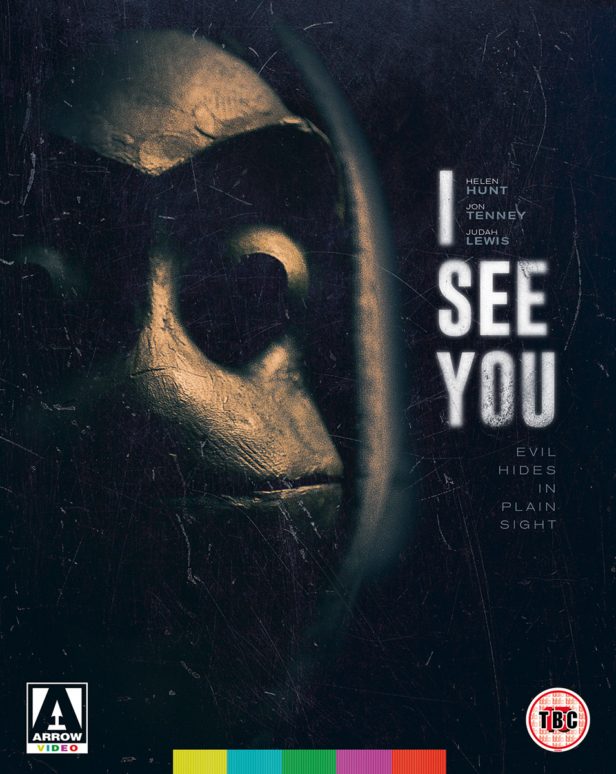

I See You is a puzzle movie where revealing the exact horror sub-genres it sticks with to the end, or even to its halfway point, constitutes as a spoiler. Penned by American actor-turned-writer Devon Graye (Dexter, The Flash), directed by Brit Adam Randall (who helmed Netflix Original sci-fi iBoy) and starring Helen Hunt and Jon Tenney, the Ohio-filmed movie benefits from knowing as little as possible, beyond the basic premise that concerns a series of abductions in a small town coinciding with the apparent haunting of a family’s home.

That said, there’s still plenty to discuss without giving the game away. Speaking to SciFiNow at last summer’s Edinburgh International Film Festival, Adam Randall (carefully) told us about his film…

How are you selling this film without spoiling it?

It’s been very difficult from the beginning, even when pitching it to people. When doing press at festivals, the running joke became: “Well, we can’t really say much about it.”

I guess the idea is that it’s sold as a horror film starring Helen Hunt, and as about a fractured relationship. She had an affair, there’s a disappearing kid, weird goings on in the house. And I guess ultimately, what connects these two story lines… But it’s tricky, because you’re almost not saying anything about one of the most interesting things about the film.

What was Devon Graye’s screenplay like when you came on board?

Very similar in terms of the structure. The way that certain things played out was slightly different. And in terms of characters, it was slightly different. But structurally, it was there with this whole peeling back of layers. I hope the audience has the experience I had reading it. You think it’s one thing and then it’s something else.

Part of the thrill with the film is how the notion of what sort of horror film you’re dealing with changes from act to act. Even the opening sequence teases something very different from that logline of Helen Hunt being terrorised in her home…

That was very deliberate. What was very important was establishing that it’s a horror film and trying to get away with as much as we possibly can. We came up with this idea because we felt like the film slightly slows down as you get to know the characters and the situation. And it feels like you really need to give the audience something or to say: “Don’t worry, this is going somewhere. There’s more going on than what you think.”

I think, thematically, the film is about evil in your own backyard, and evil that the audience, hopefully – but also the characters – believe in, as this sort of overbearing evil. This evil that’s indescribable. But by the end, you realise it’s very describable.

How did you find the house? And how much did you have to change?

I was in the UK at that point, so I asked [producer Matt Waldeck] to scout. When I first spoke to him, I said there’s no way we can get make this film without building [a house]. And then I quickly realised that was never going to happen!

So, I said, we need three things for this house: it needs to be really big, open plan and should be on the water. The really big thing was so we’d have freedom to shoot in it. If it’s all set in this house, we need to be able to shoot in an interesting way. Open plan was because I wanted it so you’re seeing characters through different rooms; that you can almost be telling different stories in the foreground and in the background. And to shoot them in a really interesting way. And then the water was partly due to this kind of American suburbia being quite familiar. So, I thought having this house by this amazing lake would give it a different feel; give it this sense of foreboding, if you will. It can look picturesque and beautiful, and then it can look terrifying.

Matt went and saw a lot of houses because he lives in Cleveland. And there was this one house that ticked all the boxes. I went and looked around, and it was perfect. But the tricky thing was the script was so specific with the house-set sequences it features.

Obviously, every film is manipulating the audience. Martin Scorsese said cinema is just what’s in the frame and what isn’t. And in this film, I thought even more so, because literally if you pan three inches to the right, it changes the whole movie. And we do a lot of changing the whole perspective in echoing earlier shots from the film almost exactly.

There’s a compelling exploration of grief, trauma and abuses of various kinds in I See You, and the knock-on effects that horrible actions have on others…

One of the ideas I found really exciting when I read the script is how we can know things subconsciously but we’re too afraid to admit them. But we act because of them. We do certain things because of them that go on to have effects. I think the characters in this are responding subconsciously to their relationships, and to what they know about one another, but refuse to actually look at it. And were they honest? Were they actually looking at each other and going: “Okay, I know who you are.” Everything could have been stopped before it got too terrible.

What was also very important was just the fallout from one person’s actions and warped desires having such a huge effect on so many people. Everyone in this film, by the end, has been deeply affected in quite a bleak way.

I See You out on Blu-ray now from Arrow Video.