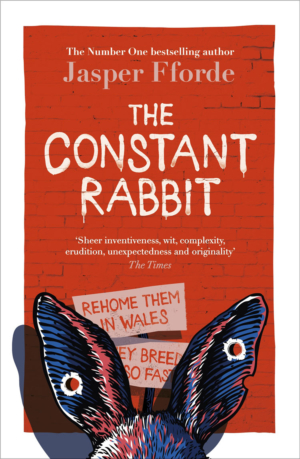

England, 2020. There are 1.2 million human-sized rabbits living in the UK. They can walk, talk and drive cars, the result of an inexplicable anthropomorphising event fifty-five years ago.

A family of rabbits is about to move into Much Hemlock, a cosy little village where life revolves around summer fetes, jam-making, gossipy corner stores, and the oh-so-important Best Kept Village awards.

No sooner have the rabbits arrived than the villagers decide they must depart. But Mrs Constance Rabbit is made of sterner stuff, and her family are behind her. Unusually, so are their neighbours, long-time residents Peter Knox and his daughter Pippa, who soon find that you can be a friend to rabbits or humans, but not both. With a blossoming romance, acute cultural differences, enforced rehoming to a MegaWarren in Wales, and the full power of the ruling United Kingdom Anti Rabbit Party against them, Peter and Pippa are about to question everything they’d ever thought about their friends, their nation, and their species.

It’ll take a rabbit to teach a human humanity…

We speak to The Constant Rabbit author Jasper Fforde about Brexit, discrimination and sexy rabbits…

How did you first get the idea for The Constant Rabbit?

I was thinking about what happened to the rabbit who starred in the chocolate Cadbury’s Caramel advert of the Eighties! It’s this ridiculous over-sexualised anthropomorphised rabbit. And I thought ‘who was she, who was this actress? What did she do afterwards? Did she get any other roles as a rabbit or was that it? Was that her amazing moment in time?’. And then the rabbits actually became a very good proxy for a demonised minority ‘other’. Because our relationship with rabbits has been so unbelievably unpleasant over the past century or two, they seemed absolutely ideal.

Rabbits are used everywhere. We have this love-hate relationship with rabbits. [There’s the] sexualisation because of the ‘breeding like rabbits’ yet at the same time we exterminate them as pests in their literal hundreds of millions. It’s a very confusing relationship.

Where did you start with the novel?

I think I started with conversations. There’s a rather nice ‘getting to know you’ dinner party between the Rabbits and Peter and I think that’s probably where it started off. I love this idea that he hears that Doc nearly served in Afghanistan and he says “no no I was nearly served up in Afghanistan!” They’re here and they’ve been here for a long time and they’re very integrated, but they’re very very different; they’re not human. They’re human-like but not actually human and that was the relationship that I wanted humans to have with rabbits. They’re not human but they seem, in every way you could possibly imagine, completely human.

It was about trying to get into the head of someone who, like Peter, essentially has leporiphobia like so many other people and it was trying to look at this bizarre sense; this hatred of the other. But trying to get in the head of the people perhaps who are doing it in a bigger way. All kinds of silliness. I just started with riffing on the characters and then it kind of just broadened and lightened and darkened as time went on.

How did you define the characteristics of the Rabbits?

If you’re anthropomorphised, you retain some of the attributes of your own species, and then you have to have something of humans as well. The question is: Which do you bring from each part of humanness and rabbitiness?

That was very interesting and there’s a lot of humour to be had in having rabbits who are slightly confused over whether they like being human or they like being rabbits. Or are proud of being a rabbit but like to be human too. Because they enjoy a lot of the trappings of being humans and as they describe it: ‘Having abstract thought is a wonderful thing to have, great fun.’ Driving round in a car, going to the cinema… tremendous. But there’s parts of it we don’t like. And I think that’s a nice little way of perhaps playing with what’s bad about humans and nice about animals. And I think it’s just finding that nice little mix perhaps of how they interact.

There is a certain event in the novel called Rabexit which is obviously a play on the UK’s own Brexit – what made you decide to include this?

I actually wrote about 20,000 words of [the novel] during the run-up to Brexit. I think a lot of how my views changed very radically over my nation and my countryman during Brexit during and after the vote. So yes that obviously clues into it, as does a lot of modern politics, even US politics, Trumpian politics comes into it as well.

Why did you set The Constant Rabbit today?

If [the Rabbits] had just arrived, it would have just been about all the euphoria over their arrival. The focus of the book would have to be on how this came about and I wanted to look more at something established. At first you go ‘wahey it’s wonderful!’. It’s like technology is to us now. You use technology and it’s all ‘wow that’s amazing it’s incredible’ and then like two weeks later it’s like ‘meh, what’s happening next?’.

Humans move on, they’re very faddy and they have different views about something from the initial excitement. I wanted to tell a story that’s 55 years on and it’s all becoming a little bit tricky because there are 0.9 milliion Rabbits and it’s become the only political issue that is actually facing the country. In the book, there doesn’t seem to be anything else going on at all. Apart from people talking about getting the Rabbits into MegaWarren. It’s that sort of over-domination of this one aspect. It just seemed so much fun with these established characters. The fact that Connie [the Rabbit] had had a small career in movies that didn’t go very well and then the rabbit Doc is retired, having been in the military. All of that long-established world that’s been worn in, like that shabby old world. You’ve seen Star Wars; I kind of like that lived-in world of established facts.

What positive aspects would you take from the Rabbitty world?

Oh the Rabbitty world! Oh I think just be nicer. I tried to make the Rabbits actually as positive and as pleasant as I possibly could make them. There’s a kind of understanding that I like about the Rabbits and they’re very un-selfish. They’re very cohesive as a whole and they look after one another and they just don’t get a lot of human things which I think is great.

I put in all these rabbit sayings, like ‘only a fool buys twice’ and they understand sustainability and they have a very broad sort of outlook on the biosphere that we all live on, whereas the humans have tunnel vision. It’s this sense of ‘I own the planet and I’m going to do things how I want’. And all these other animals that live here have no rights at all. This whole thing about hominid supremacy. Why do the other animals on the biosphere not get some kind of look in too? I think I like that most about the Rabbits – a broader sense of their place within the planet and how they should treat it.

The Rabbit culture is very detailed – especially the duelling – how did you go about creating it?

[With the duelling] the Rabbit society is very matriarchal. The chief doe employs a male rabbit, who is essentially a bodyguard, and in return, he gets mating rights. But if there’s a bigger rabbit: ‘Sorry mate, you’re done’. And you’re out.

I thought ‘well okay let’s take this rabbit system and they have to somehow square the human patriarchal system with what they think is the better system’. They get the human patriarchal system and they go, yeah, we’re not buying that, but we have to somehow square the two together so they go okay, we’re going to have marriage. We’re going to have our little nuclear families and do all that stuff, yeah great. But we’re going to maintain this notion that you can change husbands and we’re going to do it in a very gentlemanly fashion and if the doe/female agrees to it and goes ‘actually I quite like this husband; come on current husband you’re going to have to fight in a duel’. Right okay then! Pistols at dawn then and I’m going to be very British and human-like about it.

It’s the female Rabbits’ way of squaring it, squaring what they want with the males and trying to figure out a way they can make it work. But yeah if you’re a male rabbit and you’ve got a fantastic wife, you’ve got to work to keep her because if you do something wrong, that’s it sunshine you’re done, you’re finished!

One of the characters in the novel, Pippa, is a wheelchair user, but there’s never a point made about it – was that a conscious decision?

Yeah I went to see a play, I can’t remember what it was. One of the handmaidens who was an extremely good actress was a wheelchair user and when she came on stage for the first time it was like ‘woah, didn’t expect that’ (well you should do with the RSC because they’re brilliant with those sort of things) and then all of a sudden within 20 seconds, she’s starting to deliver her lines and it doesn’t matter. She comes on again and you’ve just forgotten. You’re suddenly thinking to yourself ‘why has it taken until 2020 for actors who use wheelchairs to even be considered like this?’ And then I thought: ‘Hold on, I don’t have any characters ever who use a wheelchair’ and then I thought ‘okay, lets put one in but it’s not important, it really is completely irrelevant to Pippa it doesn’t matter to her, it doesn’t matter to the Rabbits. It doesn’t matter to her father. It just is’. She’s a totally normal, interesting lovely girl and it’s irrelevant and it’s that irrelevance that I wanted to bring across in the book. The ordinariness of her and that nobody actually cares at all.

We liked how the protagonist, Peter, is likable but he’s not really your typical hero…

He’s very likeable, he’s quite funny and he’s obviously a good bloke, but he’s kind of a little bit spineless. He believes he’s not leporiphobic and he’s clearly extremely complicit in everything that’s been going on with the anti-rabbit task force. I wanted him just to be someone who could have a realisation but is utterly flawed. His realisation also does not so far lead to action and I think that was important too. I didn’t want him as a saviour. You can be a good person and have flaws and you can realise it’s wrong and you’re not sure what to do.

I like him and I think flawed characters are good. I think a lot of my are characters are very much strong female leads but the story is about the secondary male character who really really likes the strong female lead, which for me is more important. A lot of my male characters are like that. Yes you can write strong female leads and role model leads and that’s very important but equally as important – if not more important – is to have secondary male roles who are okay and can celebrate a strong female lead. Who doesn’t mind being secondary to them and understands and appreciates it. So I think there’s that theme coming into it as well. So yeah I like him.

The book has some Orwellian references. Were there any other inspirations for The Constant Rabbit?

I was reading up a lot about discrimination and prejudice in the UK and what that means. There was a lot in the newspaper happening at the time. Yeah there was quite a lot of reading but it’s a difficult book to write because I’m obviously (not obviously) but I am as I describe it; I won the lottery without actually buying a ticket. Being male, middle class, living in Europe, with money and private education – the whole number. So I can’t really write about discrimination from the point of view of someone who is being discriminated against but I think I can write from the point of view of someone who is complicit within a discriminating society. Because I’ve accrued the benefits. Historically and ongoing. And that’s very much from where the viewpoint is and Peter Knox’s view is. It’s very much from the human side of the discriminators rather than the discriminatees. That was a difficult toss-up for me but it was really coming from that point of view.

The Mallet brothers [in the novel] are, I think, are the only characters I’ve ever written who have no redeeming features. Usually, I have baddies who have at least some redeeming features but the Mallet brothers don’t have any. They talk about preserving the cultural heart of the village and whilst that has positive connotations it can have very negative ones as well. This is an area I know very well around Powys and Herefordshire; people here are very keen on having garden fetes and the best-kept village awards, these sorts of little things. Which there’s nothing wrong with. It’s to be applauded. It’s nice to be able to do these things. But on the other side of the coin, there is also a very insular approach and when outsiders come in, that can be troublesome and difficult and challenging to the people who have perhaps quite very narrow opinions.

There are heavy themes in the book but it’s also incredibly funny. Was setting the right tone in the novel important to you?

Tone is probably what I struggled with more than anything. The difficulty is that if you mix comedy with some very serious subjects, then there is the risk of saying that these subjects are not serious, they’re frivolous. And if you make jokes using these ideas, then all of a sudden it’s a frivolous book and it’s dismissing very important issues and that’s a difficult one to square sometimes.

I was kind of heartened by someone who said ‘doesn’t M.A.S.H do that?’ and I went ‘oh yeah, it does actually’. This sense of tragic comedy; so long as they’re not making jokes about the issue. Sometimes its very close. What’s most [nerve-wracking] for me is that this book comes and then people will be saying ‘no no no this doesn’t work at all it’s horrible’ or ‘yes it works totally’ and I can’t know that until it’s out there. But trying to get the tone right, trying to say ‘okay this bit is comedy and this is clearly not comedy’ is a very difficult balancing act to do.

I went over it a lot. There are huge bits that I took out because I thought they were just too close to the bone. It’s very difficult, it’s very subtle but there are all manners of little bits here and there where I thought I’d just gone over the edge. I don’t know [but] writing without risk is not really writing to be honest. And what’s the worst that can happen? Me, who won the lottery without buying a ticket gets to feel a little bit sad? Well boo hoo.

There’s a religious element to Rabbit culture. Why did they not adopt a human religion?

If cows had gods they would be shaped like cows. I have nothing against people who have a faith. I don’t believe it and to me a human is very much invented by humans, male humans as well. I think with that being said, then surely a rabbit religion would be along rabbit lines and that makes total sense to me. And the following they have is very much along rabbit lines. It seems very positive actually. Very positive to them and very positive in general. Just this unifying theme among rabbits that there’s this the circle – because Lago (the original Rabbit) got caught in a snare, the circle then became the symbol of their religion. It kind of fitted together that instead of the cross you would have the circle. So no it made complete sense, why would they worship a human god? It doesn’t make any sense at all.

What’s next for you?

Well, my inbox is full of emails saying ‘when are you going to write the sequel to…?’ and there’s like three different books, well four actually. I think the next four books will be sequels. I’m working on the last book in the Dragon Slayer series Trolls V Humans it might be called. And then I’ll be doing the second book and hopefully last book in the Shades Of Grey series and then Thursday Next and then eventually the Nursery Crimes series.

I think that will be fun because I’ll be going back to well-worn characters that I know really well. Shades Of Grey is one that I get a lot of flack about – the fact that there hasn’t been a sequel and I said there was going to be! I like it as a book; it’s a good book which is unusual for me because I don’t generally think my books are very good but I do like Shades Of Grey. I like The Constant Rabbit too actually. But yes I’ve got to write a sequel to that.

What is the difference between writing a sequel and a standalone novel?

It’s very different actually, very very different. The great thing about writing a new book is that you are exploring from scratch. You’re going down that rabbit hole [ho ho!] and you’re discovering all these things for the first time. And you’re going ‘yeah I can do this and do that’ and that’s great fun and it’s very hard work.

[The Constant Rabbit] is really a world-building book. All of my books are in worlds that I had to create from scratch, essentially, and creating the rabbit world/human world was very exciting, and it was very interesting to see how the interactions worked. But then that’s really hard work.

I also like sequel books because you’ve got this wonderful continuity that you have to work with. And also a lot of the storytelling grammar. If people have read all seven of the Thursday Next books then I can do a lot more with it because there are all kinds of things that the readers totally get already that don’t need to be covered again. I can just say ‘okay we’re doing this, doing that and I’m going to reference a book, two books away – there’s something that was happening in Book Two that’s now going to be resolved’. It’s a very satisfying read I hope and also it’s very satisfying for me to put together. You’re kind of juggling with nine balls and that’s quite fun to do. Both have their benefits, I think. But having done The Constant Rabbit I think I’m going to maybe concentrate on writing sequels for a bit.

The Constant Rabbit by Jasper Fforde is out now from Hodder & Stroughton. You can read our review of the novel here.