Halloween is just around the corner, and this year Chills In The Chapel has a very special event lined up. Legendary composer and sound designer Alan Howarth will be performing on 30 and 30 October, playing his Escape From New York score and a series of his collaborations with the great John Carpenter.

Howarth worked with Carpenter on Escape From New York, the Halloween sequels, Big Trouble In Little China, They Live and more, and as a sound designer he worked on the very first Star Trek movie.

We took the chance to talk to Howarth about what audiences can expect at Chills In The Chapel, his collaboration with Carpenter, and how he feels about the revival of synth scores in horror.

Could you tell us about the event coming up?

I was approached to come to London for 30-31 October and we’re going to do two concerts there. On 30th we’re going to screen Escape From New York and I’m going to be set up on stage with my electronic music rig, and actually play along, sort of improvise on top of the soundtrack while the movie plays. So it will be Escape From New York plus a live performer and that will be a lot of fun.

And then Halloween is 31 October, and in this case we’re going to break out into all the horror movies I’ve done with John Carpenter and some other ones I’ve done on my own since then, and have a lot of fun while being Halloweened!

What’s the experience of performing your scores live like?

It’s what you already know, obviously the soundtrack cues, there’s the music featured instead of a background piece, and then I have a VJ, a lady named Jade Boyd, and she’s made videos that go with the performance that we run behind me. But it’s been VJ-ed so it’s very abstract, it’s essence of the films, it’s very artsy. It’s a lot of fun. The soundtrack’s enhanced with extra visuals and my live performance; I come from the world of jazz so improvisation is the way I do it. No two concerts are ever the same because I’m live playing whatever comes into my head at the time.

You compose scores, work as a sound designer, and you’re a live performer. Do they feel separate or does it all feel like elements of the same experience?

It does kind of feel like one world to be honest with you. It’s the same instruments; it’s just where we focus. It’s kind of like being an interior decorator, I’m either working on the living room or the basement or the whole house. Same tools but different focus. In the world of sound design I started out making science fiction effects. I worked on the first Star Trek to create the Enterprise and the transporters and the lasers and the monsters. This was before there were libraries of sound effects that you could use. 30 years later, all these sound effects are available in different flavours in different sound effects libraries. To create a new sound isn’t quite as necessary as it was in those days.

However, I do enjoy when somebody says “I need something new,” or “There’s something I’m looking for that’s not in the library, I need you to go record a thing.” And it’s all storytelling, right? Even to make the sound of a dinosaur walking in the jungle, and crunching everything around it and eating a guy, is a sound design and in some ways you could think of it as a piece of music, really. The most basic definition of music is the alternation of sound and silence, so it’s pretty wide open. So what sounds are you making at the time, is sound design music? In my world, yes.

There’s definitely been a wave of films recently that have been heavily influenced by your work with John Carpenter, with stripped-down synth scores. How does it feel do see your impact in that way?

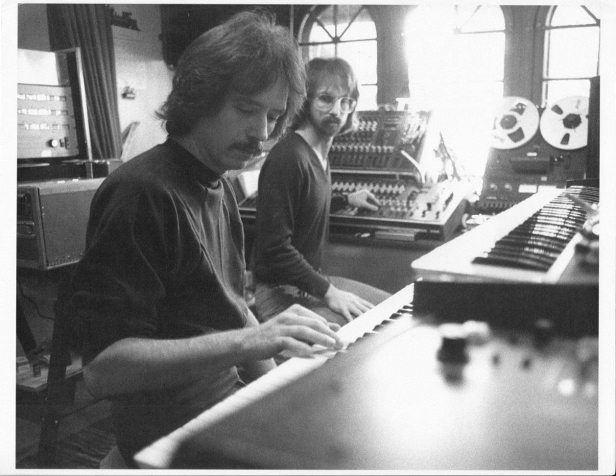

Well, it’s gratifying, I’ll say that. At the time we were doing it we were just a bunch of guys sitting in a studio. I had all the gear, I was the equipment nut. John Carpenter had the movie; in fact he wanted nothing to know about the equipment. Occasionally I’d try to explain to him “This is how…’ He says, “Alan, I don’t even want to know. That’s your job.”

So he was happy to just see the black and white notes and press notes. Meanwhile the whole synth world and the oscillators, the sequencers, the drum machines and the recorders and the mixing and all that stuff, that was my world. When we came together we got this sum, which was his mastery of filmmaking, and then his personal musical direction that he wanted to take things in, and then my ability to be the other guy in the room and work with him. Then, as we grew, he gave me more and more latitude to create more stuff. John Carpenter himself was a master of themes, but back to the idea, we were just a couple of guys doing it, so to have this conversation, here we are 30 years later and still be talking about it, we must have done something right, huh?

Could you tell us how you first came to work with Carpenter?

It was a series of relationships that sort of manifested there. Started out by getting on board the first Star Trek movie, and the picture editor from that, fellow named Todd Ramsay; his next assignment was Escape From New York. So he was on board with John Carpenter as the picture editor, and he liked me, he felt I had some talent. So whatever scheduling issues [Carpenter] had with his former collaborator, fellow named Dan Wyman, there was an opportunity to look at someone else, so Todd Ramsay recommended that John Carpenter check me out.

He came over to my little rented house in Glendale, California, all my stuff was set up in the dining room from doing Star Trek, and he sat down with me for an afternoon, and I shared some of my music and played him some of my sounds and when he’s getting ready to leave he goes “This is cool. Let’s do it.” And that was it. He just said “Let’s do it,” that was the opening of the door to my working with John Carpenter. Then we jumped into Escape From New York, which was my first film score. I learned a lot from John Carpenter being in a very privileged school of one. Initially my job was to make sure the red light was on when he was playing but then started building tracks, working with drum machines and sequencing, putting a lot of the synth palette in front of him that I knew how to do, and he’d go “That’s cool, we’ll use that, let’s do that.”

So that this collaborative things started happening. At the time we didn’t know what we were doing, we were doing it intuitively. My next score from him was Halloween 2, where he was now committed to making The Thing which was a very challenging production, they had to go to Alaska, British Columbia, so at the end of Escape From New York, he just sort of looked at me and said in a casual way “In case you didn’t know, you’re going to be the Halloween guy because I’m going to busy.” So I inherited Halloween 2 from him. We used his iconic Halloween themes and I used that as a model, but then I dubbed in all of my new synth technology of the day on top of them and gave the score for Halloween 2 a more Gothic feel.

There’s definitely an evolution to the Halloween scores.

John Carpenter made Halloween in the beginning never expecting any sequels, then the producers wanted to do another one, so he said “I guess, OK,” and then we came to Halloween III, and now he wanted to let go of Michael Myers and go off into a Halloween anthology where every year you make a new Halloween story, so Halloween III takes place on Halloween but it doesn’t have Michael Myers. If it wasn’t called Halloween III and was just called Season Of The Witch, it would probably be taken as a fine movie and in retrospect it was a fine movie, but it was considered a flop because the Halloween community who wanted Michael Myers, he wasn’t in it so they hated it at the time.

So he was done fooling around with Halloween with Halloween III, so when they wanted to pick it up again and make Halloween 4, 5, 6 and beyond, he was done with it. His posture was “Send me my cheque, you guys do what you want.” We were working on Big Trouble In Little China at the time and I was approached to do Halloween 4. In the studio I said “Hey John; they want to do Halloween 4, would it be OK with you if I did it?” He said “Hey man, do whatever you want. Knock yourself out.” So that’s where I picked up with Halloween 4 and then did 5 and 6, that sort of trilogy of those three Halloweens that were made in the late ’80s, early ’90s and then another regime of people, new directors, producers came in for Halloween 7 and beyond and they continued with sequelitis since then.

It’s great to see the reevaluation of Halloween III, it’s a great film and the score is fantastic!

It was considered a flop but a lot of people come back to me still saying that the score for Halloween III is some really great synth scoring and very inspirational. It has its dark qualities to it and its own unique footprint. I remember sitting down with John Carpenter to start the score for Halloween III, which was the only part he wanted to participate in, the music, otherwise didn’t want anything to do with it directly, and we sat down and we played the latest Tangerine Dream LP at the time, just to listen to, they were great synth masters, and he looked at me and said “OK, hey, Alan, this is going to be really easy, we’re just going to rip ourselves off.” Which was his way of saying “I was very pleased with what we did with Escape From New York, let’s just keep doing more of that, whatever it is.”

So we just sat down and I’ve got to say that the whole time I worked with him, it was some of the best times of my life. We just had fun. It wasn’t stressed out. Carpenter told me that doing the music for his movies was like taking a vacation. As opposed to being responsible for the edit and the studios and the distribution and the marketing and and all the other stuff of being a filmmaker, he could kind of turn the phone off, hide in my studio and just play music, he would really enjoy himself.

I can imagine that working on Big Trouble In Little China must have been a nice change from the work you guys had been doing together.

Yeah, exactly. Right after Christine we did Big Trouble In Little China, and of the scores that we did together, both he and I will agree that’s probably our best score for two reasons. One, the nature of the movie had more than just horror in it, so we could do action, adventure, comedy, scares, all kinds of stuff. Then we had the longest period of time to work on it, so it had the most production involved. Usually we’d get six to 10 weeks on a score and we had 14, so we had another month. It’s really the most elaborate score, as a standalone. At the time the box office was considered a flop but it wasn’t and now it has an afterlife in this whole world of DVD, video and now Netflix, etc.

Finally, is there one score or film that you worked on that you feel doesn’t get the love it deserves?

I think one of the great scores that I did with Carpenter that sort of lays out there is Prince Of Darkness. The movie itself is a medium weight, successful to a degree, but actually there was an article that was published in like 2001, somebody did an article of the top 100 film scores of the 20th century, and Halloween was in there for sure but honourable mention, like 105, was the Prince Of Darkness score. The world of sampling had been fully fleshed out and we had some good samples of voices and choirs and stuff like that, which we used. And fooling around with the devil was a lot of fun to do, a different kind of horror movie, semi-religious overtones. That was cool.

And one more tag on that, the other one is They Live. Now I see kids walking around with these t-shirts with the iconic moment of OBEY with an alien’s face on it, and that movie was…golly, cardboard cities in Los Angeles? What we have today? It was amazing, the vision there. We had drones in the film, right? Cops had drones. So there’s a lot of very futuristic vision of a current reality.

You’ve got to acknowledge Carpenter as one of the great filmmakers of all time. He’ll go down in history as that guy. And musically the scores are minimalistic so it’s not like we’re Hans Zimmer with a 100 piece orchestra and a 50 piece choir and this production horsepower behind our notes. We did it minimally but it works!

Chills In The Chapel with Alan Howarth is on 30 and 31 October and you can find more information here. Keep up with the latest genre news with the new issue of SciFiNow.