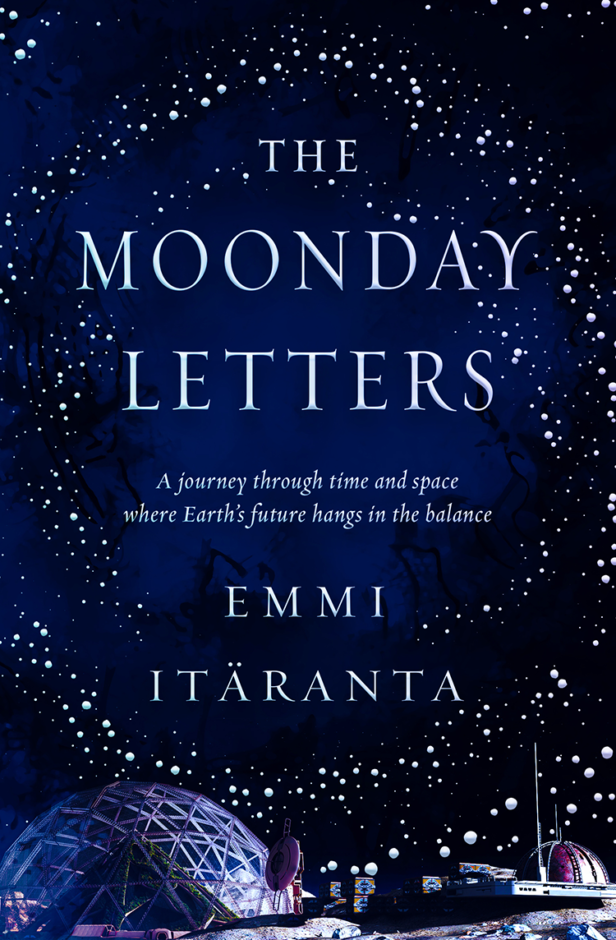

Out next summer, Emmi Itäranta’s The Moonday Letters is sci-fi mystery and LGBTQIA love story set across Earth and Mars and we’re delighted to exclusively reveal its cover (above) AND give SciFiNow readers a sneak peek into the novel with an exclusive excerpt!

The Moonday Letters follows Lumi, an Earth-born healer whose Mars-born spouse Sol disappears unexpectedly on a work trip. As Lumi begins her quest to find Sol, she delves gradually deeper into Sol’s secrets – and her own.

While recalling her own path to becoming a healer under the guidance of her mysterious teacher Vivian, she discovers an underground environmental group called Stoneturners, which may have something to do with Sol’s disappearance. Lumi’s search takes her from the wealthy colonies of Mars to Earth that has been left a shadow of its former self due to vast environmental destruction. Gradually, she begins to understand that Sol’s fate may have been connected to her own for much longer than she thought…

Can’t wait until next year to find out more about The Moonday Letters? Don’t worry, we understand. Luckily you can sit back and enjoy an excerpt from the novel right here, which sees an interview into sustainability on Mars…

Mars Universal Media Network

Current affairs programmes

Channel 12

Mars Mirror

Transcripts

Thursday 6.3.2168 CE

Interviewer: Arcturus Teng

Interviewee: Sol Uriarte, Ethnobotanist, University of Harmonia

AT: Good evening from Datong. Leading researchers from universities all around the Solar System have gathered here for an interplanetary symposium looking at food management on Mars. Ethnobotanist Sol Uriarte, who is one of the keynote speakers, is with us tonight. Dr. Uriarte, you specialised in plant grafting and disease resistance. What do you see as the most burning questions in maintaining the self-sufficiency of Mars?

SU: Now we must keep in mind that Mars achieved self-sufficiency decades ago. There is no reason whatsoever to believe that this situation is under any kind of threat. Mars is capable of producing more food than it needs, and in fact frequently does so. Due to effective zero-waste systems the surplus is utilised and recycled for other purposes, such as raw material for biofuels. Under the circumstances the question we should be asking is, how can – how do – we redirect some of the resources invested in food production on Mars.

AT: But is it not true that the flow of refugees from Earth to Mars in the past years has caused some concern over food security on the Red Planet? The issue of protecting the robotic farms from plant diseases or harmful invasive species potentially carried from Earth has also been raised. Sol Uriarte, what is your view on this?

SU: Naturally, we must ensure that we keep up the current standards, and that the quarantine regulations are regularly checked and updated. But as long as the system we have built over the past century remains functional, Mars can afford to offer refuge to those who need it. And furthermore, we can afford to double or treble our contribution to interplanetary humanitarian aid.

AT: Redirecting some of the Martian resources outside the planet is a highly controversial issue. Are you saying you are in favour of it?

SU: Yes, absolutely. In particular, I believe Mars should be providing humanitarian aid to Earth and the colonies of Enceladus.

AT: But we already are, is that not correct?

SU: Our current annual contribution is zero point thirty-nine percent of all of combined gross national product of Martian city states. In comparison, we spend two hundred times that money manufacturing weapons that are mainly exported to Earth, mostly to the worst-polluted areas where unrest and conflicts are common. These include the vast refugee camps around the major spaceports in Florida, Kazakhstan and Inner Mongolia.

AT: Some would argue that the self-sufficiency of Mars is the result of longtime work that has required great sacrifices. Shouldn’t Mars put its own population first?

SU: Aren’t we already doing that? Mars owes everything to Earth. For the longest time, we were entirely dependent on their assets and only survived thanks to them. Martian wealth and wellbeing are based on systematic long-term exploitation of Earth’s natural resources. It is time we acknowledged our role in amplifying the problems on Earth. It is vital to remember that the survival of the human species during crises, such as wars and pandemics, has been enabled first and foremost by our ability to feel compassion and offer help.

AT: There are surely those who would challenge that view. Many people on Mars feel that by opening our spaceports to migrants, we are risking our hard-gained ability to dwell on a planet that does not provide any prerequisites to support life. Many of the new arrivals are not entering via carefully defined quotas, but are instead coming through illegal routes and cannot be easily deported. Food supply is not the only concern, but housing and employment are also at risk.

SU: As I already pointed out, the food supply concerns are based on a myth that has no basis in the current reality. The wealthiest portion of Martian population has a lot more living space than they need. This is also detrimental to energy efficiency. As to the job market, there are several sectors where Mars is actually short of workers, so these so-called risks seem as asinine, pardon, artificial as the beliefs about food supply.

AT: Sol Uriarte, you were a last-minute replacement for Professor Min-soo Jung from the University of Harmonia as a keynote speaker. I understand that the choice stirred dispute in some circles. You are known as something of a rebel in the scientific community. Would you like to comment on this?

SU: I have always been open about supporting equal rights for all living beings. What kind of a person would I be if I didn’t support that goal? And I do not exclude the eco-philosophical view that intact landscapes have rights too, whether they are living or not.

AT: We are unfortunately running out of time. Sol Uriarte, is there one last thing you would like to say to citizens who may be concerned about the situation on Mars or Earth?

[Transcriber’s note: At this point Dr. Uriarte turned to look directly at the camera, an action that journalists routinely advise against.]

SU: Earth wakes and stones will speak, and dark recedes over waters.

AT: (long pause) That… is certainly a very poetic way of expressing it. Thank you, ethnobotanist Sol Uriarte.

(end of interview)

6.3.2168

Halley 105 Hotel

Datong, Mars

Later

Sol,

As I write this, you have yet to respond to the messages I sent you one after another. But I can see you have read them. That gives me some peace. I want to think the only thing parting us is a delayed message, and some unexpected obstacle.

After all, it has happened before.

((#####))

After the news report finished, I left the screen on for a while. The strange sentence you’d spoken sounded vaguely familiar to me, especially the first part.

Earth wakes and stones will speak.

It was as if I had read it somewhere, or heard someone else use it a long time ago.

A brief section of Earth news followed. In Barrier Reef Land there had been an uprising of workers demanding better food, because a few of them had died from a poisoning caused by contaminated fish. The riots had claimed ten victims. Hollywoodland had been left unexpectedly without electricity for nearly two days, and some tourists had had to delay their return to Mars and the cylinder cities. In the largest conservation area of South America the populations of several near-extinct bird species had begun to grow. In Paris 3 the managers of the holiday isle had been mailed strange envelopes filled with tree seeds. The contents were still being studied. The police were looking into a connection with similar incidents last year in Seoul and the Vacation Archipelago of Londons.

I thought of my parents in Winterland. I wondered how much they knew about all this. Or how little.

The transmission moved via the studio to a football field where players wearing red and purple shirts were running around against green. I switched the screen off. Ziggy, who had been sleeping curled into a ball in an armchair, raised his head, jumped to the bed and climbed onto my lap. I stroked his orange-and-white back.

I decided I needed to get out. The conference centre where the symposium was being held was not far. I could make it there before the final panel discussion ended and surprise you. Just in case, I sent you a message, left a handwritten note on the bed and notified the reception there was a cat in the room that shouldn’t be allowed to escape in the event of opening the door.

High above the streets the glass domes were beginning to dim into evening-time lighting. I have always preferred Datong after dark: it is a vast improvement on the purely functional brutalism of the daytime, where every last bit of wear and tear is visible, the fact obvious that at the time of the construction of the city Mars could not yet afford luxury. Datong has none of the splendour of Harmonia, but in the dusk it looks almost beautiful.

On the way I stopped to buy green tea in my fumbling Chinese. Along the streets merchants were pitching stalls, placing various foods on display: corn bars, grasshopper wafers, hot and cold drinks. Bright-coloured greetings in various languages were painted on the grey canvas walls: 歡迎! Welcome! !الهس والهأ Добро пожаловать! Bienvenidxs! Bienvenue! Murmurations of starlings wafted like smoke above the rooftops. Faded blossoms had fallen from a vertical garden on the side of a tall building to cover the street. Their brown petals were crushed into the surface of the pavement.

((#####))

The conference centre was huge, but after a bit of wandering about I found a sign that announced the Food Economy Research Symposium was in progress in the East Wing. The final session of the day was finishing. I stayed in the foyer and waited. In front of the tall windows on a long bench sat a woman who had covered her hair with a dark blue, star-patterned scarf. Her pen swung from side to side as she wrote on her portable screen, looked at what she’d written and puckered her lips. A couple of guards kept watch by the doors. On the curved external wall of the auditorium, three pairs of doors remained closed. When the clock struck seven, they opened, and people began to pour out. I looked for your dark hair and angled shoulders in the crowd, Sol, the bright purple shirt you had worn in the interview.

The stream of people narrowed down and trickled away, but I did not see you. I looked around and noticed a university colleague of yours in the vicinity of the front doors. I had met her a few times. I tried to remember her name – Leyla? The woman who had been writing on the bench had got up and was chatting with your colleague. Their lips moved, but I could not hear the words. They both burst into laughter. I approached them. Leyla glanced my way and noticed me. I reached out my hand.

“Hi, Leyla,” I said. “I don’t know if you remember me, I’m –”

“Of course,” Leyla said. “Sol’s spouse. What a nice surprise to meet you again.” She shook my hand, but there was something slightly strange about the way she looked at me, an undercurrent I could not quite catch. “This is my friend Enisa Karim.” The woman shook my hand and a dimple appeared on her cheek. “And this is…”

Leyla trailed off. I realised she had forgotten my name.

“Lumi,” I said. “Nice to meet you.”

The guards were beginning to close the double doors on the wall.

“Is Sol still in the auditorium?” I asked.

Leyla’s eyes shifted a little in Enisa’s direction. A small crease appeared on her forehead. Enisa spoke.

“Didn’t they leave after the interview?” she asked. “Over an hour ago?”

“They did,” Leyla said. “That’s why I was surprised to see you here.” She directed these words at me.

Enisa noticed my confusion.

“Oh, sorry. I’m a journalist. I was meant to interview your spouse, but Channel 12 managed to somehow cut in and I lost my chance.” Her mouth made a tight line. The dimple vanished.

“Sol and I must have crossed,” I said. “If for any reason you see them, could you let them know I’m waiting at the hotel?”

“Of course,” Leyla replied. “I hope you find each other.”

The foyer was empty now, save for the three of us and one guard who hovered near the exit, giving us the occasional decreasingly subtle stare. The doors to the auditorium had been locked. The lights began to switch off, leaving us in a small pool of dim glow, outside which the corners could have hidden a lost shadow of any shape.

I took my leave.

I returned to the hotel as quickly as possible. When I opened the door of the room with caution, Ziggy tried to slip away into the corridor. I scooped him up, held him with one arm and pulled the door closed with my other hand.

Your coat and suitcase were gone, Sol. I looked in the bathroom and wardrobe. You had not left a trace behind; it was as if you’d never been to the room at all. The only thing hanging in the wardrobe was the threadbare cardigan I’d brought from Earth. Behind it, something did not look right: the angles of light and shadow, the shape of the wall. It was as if the space had slipped out of joint, but only a little, almost unnoticeably.

The safe.

As a precaution, I had placed the locked box you’d asked me to bring in there. I had keyed in a number code on the old-fashioned keypad of the safe, and tried the door to make certain it was locked. Now the door was ajar. I pushed the cardigan on the hanger aside, reached for the safe and pulled the door wide open.

The safe was empty. The wooden box was gone.

Sol, only you know I always use your birthday as the PIN code.

The Moonday Letters by Emmi Itäranta will be released on 5 July 2022 from Titan books. Pre-order here.