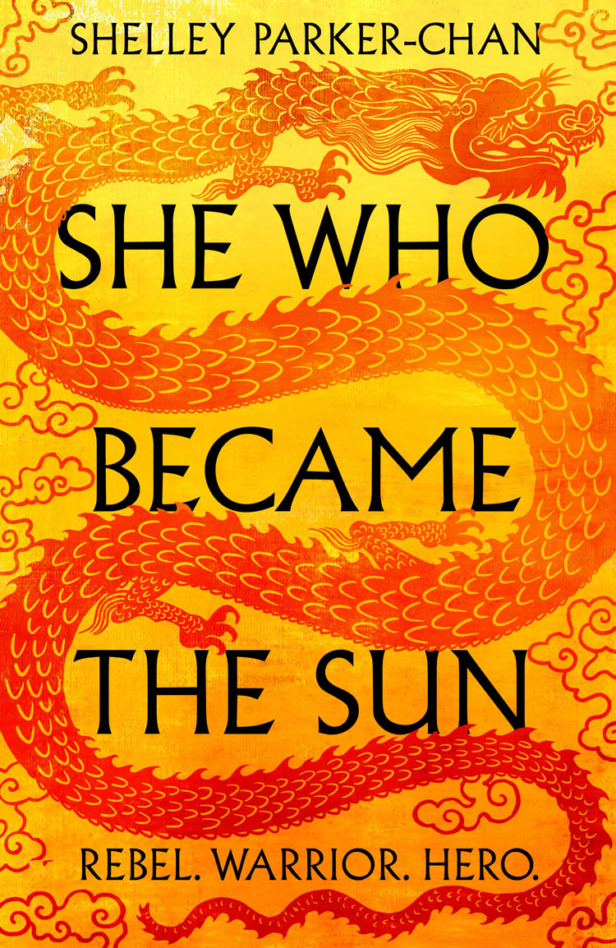

Out in 2021, She Who Became The Sun is an epic historical fantasy by Shelley Parker-Chan and we’re delighted to reveal its beautiful cover designed by Mel Four (@book_covers_etc)!

“I was yearning for a sweeping, high stakes, historical epic with the hyper-emotionality of a romance — but which also queered gender roles,” Shelley Parker-Chan tells us when we ask her how she first thought of the story. “My stories germinate from a loose nucleus of theme and emotion — in the case of She Who Became The Sun, it was gender and shame…”

Read the full synopsis of the book here…

She’ll change the world to survive her fate …

In Mongol-occupied imperial China, a peasant girl refuses her fate of an early death. Stealing her dead brother’s identity to survive, she rises from monk to soldier, then to rebel commander. Zhu’s pursuing the destiny her brother somehow failed to attain: greatness. But all the while, she feels Heaven is watching. Can anyone fool Heaven indefinitely, escaping what’s written in the stars? Or can Zhu claim her own future, burn all the rules and rise as high as she can dream?

She Who Became The Sun is a re-imagining of the rise to power of Zhu Yuanzhang, who was the peasant rebel who expelled the Mongols, unified China under native rule, and became the founding Emperor of the Ming Dynasty: “Zhu Yuanzhang started life as a starving peasant orphan and rose to become the tyrannical founding emperor of the Ming dynasty,” Parker-Chan continues. “The really interesting thing for me was: he was a novice monk in his youth. How the hell does a monk build an army that takes down an empire?

“For that matter, how does a peasant formulate the desire to become the Emperor? I was fascinated by what kind of person that would be. And to make it even more interesting, because Zhu Yuanzhang as emperor is the centre around which the Confucian patriarchal world order revolves, I wondered: what if that person wasn’t a man?”

Just as excited as we are to read She Who Became The Sun next year? Not to worry! We have the first chapter of the book right here to tide you over until its release…

CHAPTER ONE: HUAI RIVER PLAINS, SOUTHERN HENAN, 1345

Zhongli village lay flattened under the sun like a defeated dog that has given up on finding shade. All around there was nothing but the bare yellow earth, cracked into the pattern of a turtle’s shell, and the sere bone smell of hot dust. It was the fourth year of the drought. Knowing the cause of their suffering, the peasants cursed their barbarian emperor in his distant capital in the north. As with any two like things connected by a thread of qi, whereby the actions of one influence the other even at a distance, so an emperor’s worthiness determines the fate of the land he rules. The worthy ruler’s dominion is graced with good harvests; the unworthy’s is cursed by flood, drought, and disease. The present ruler of the empire of the Great Yuan was not only emperor, but Great Khan too: he was tenth of the line of the Mongol conqueror Khubilai Khan, who had defeated the last native dynasty seventy years before. He had held the divine light of the Mandate of Heaven for eleven years, and al- ready there were ten-year-olds who had never known anything but disaster.

The Zhu family’s second daughter, who was more or less ten years old in that parched Rooster year, was thinking about food as she followed the village boys towards the dead neighbor’s field. With her wide forehead and none of the roundness that makes children adorable, she had the mandibular look of a brown locust. Like that insect, the girl thought about food constantly. However, having grown up on a peasant’s monotonous diet, and with only a half-formed suspicion that better things might exist, her imagination was limited to the dimension of quantity. At that moment she was busy thinking about a bowl of millet porridge. Her mind’s eye had filled it past the lip, liquid quivering high within a taut skin, and as she walked she contemplated with a voluptuous, anxious dreaminess how she might take the first spoonful without losing a drop. From above (but the sides might yield) or the side (surely a disaster); with firm hand or a gentle touch? So involved was she in her imaginary meal that she barely noticed the chirp of the gravedigger’s spade as she passed by.

At the field the girl went straight to the line of headless elms on its far boundary. The elms had once been beautiful, but the girl remembered them without nostalgia. After the harvest had failed the third time the peasants had discovered their gracious elms could be butchered and eaten like any other living thing. Now that was something worth remembering, the girl thought. The sullen brown astringency of a six-times-boiled elm root, which induced a faint nausea and left the inside of your cheeks corrugated with the reminder of having eaten. Even better: elm bark flour mixed with water and chopped straw, shaped into biscuits and cooked over a slow fire. But now the edible parts of the elms were long gone, and their only interest to the village children lay in their function as a shelter for mice, grasshoppers, and other such treats.

At some point, though the girl couldn’t remember exactly when, she had become the only girl in the village. It was an un- comfortable knowledge, and she preferred not to think about it. Anyway, there was no need to think; she knew exactly what had happened. If a family had a son and a daughter and two bites of food, who would waste one on a daughter? Perhaps only if that daughter were particularly useful. The girl knew she was no more useful than those dead girls had been. Uglier, too. She pressed her lips together and crouched next to the first elm stump. The only difference between them and her was that she had learned how to catch food for herself. It seemed such a small difference, for two opposite fates.

Just then the boys, who had run ahead to the best spots, started shouting. A quarry had been located, and despite a historic lack of success with the method, they were trying to get it out by poking and banging with sticks. The girl took advantage of their distraction to slide her trap from its hiding place. She’d always had clever hands, and back when such things had mattered, her basket-weaving had been much praised. Now her woven trap held a prize anyone would want: a lizard as long as her forearm. The sight of it immediately drove all thoughts of porridge from the girl’s head. She knocked the lizard’s head on a rock and held it between her knees while she checked the other traps. She paused when she found a handful of crickets. The thought of that nutty, crunchy taste made her mouth water. She steeled herself, tied the crickets up in a cloth, and put them in her pocket for later.

Once she’d replaced the traps, the girl straightened. A plume of golden loess was rising above the road that traversed the hills behind the village. Under azure banners, the same color as the Mandate of Heaven held by the Mongol ruling line, soldiers’ leather armor massed into a dark river arrowing southward through the dust. Everyone on the Huai River plains knew the army of the Prince of Henan, the Mongol noble responsible for putting down the peasant rebellions that had been popping up in the region for more than twice the girl’s lifetime. The Prince’s army marched south every autumn and returned to its garrisons in northern Henan every spring, as regular as the calendar. The army never came any closer to Zhongli than it did now, and nobody from Zhongli had ever gone closer to it. Metal on the soldiers’ armor caught and turned the light so that the dark river sparkled as it crawled over the dun hillside. It was a sight so disconnected from the girl’s life that it seemed only distantly real, like the mournful call of geese flying far overhead.

Hungry and fatigued by the sun, the girl lost interest. Holding her lizard, she turned for home.

At midday the girl went out to the well with her bucket and shoulder pole and came back sweating. The bucket got heavier each time, being less and less water and more and more the ochre mud from the bottom of the well. The earth had failed to give them food, but now it seemed determined to give itself to them in every gritty bite. The girl remembered that once some villagers had tried to eat cakes made of mud. She felt a pang of sympathy. Who wouldn’t do anything to appease the pain of an empty stomach? Perhaps more would have tried it, but the villagers’ limbs and bellies had swelled, and then they died, and the rest of the village had taken note.

The Zhu family lived in a one-room wooden hut made in a time when trees were more plentiful. That had been a long time ago, and the girl didn’t remember it. Four years of desiccation had caused all the hut’s planks to spring apart so that it was as airy inside as outside. Since it never rained, it wasn’t a problem. Once the house had held a whole family: paternal grandparents, two parents, and seven children. But each year of the drought had reduced them until now they were only three: the girl, her next-oldest brother Zhu Chongba, and their father. Eleven-year-old Chongba had always been cherished for being the lucky eighth-born of his generation of male cousins. Now that he was the sole survivor it was even clearer that Heaven smiled upon him.

The girl took her bucket around the back to the kitchen, which was an open lean-to with a rickety shelf and a ceiling hook for hanging the pot over the fire. On the shelf was the pot and two clay jars of yellow beans. A scrap of old meat hanging from a nail was all that was left of her father’s work buffalo. The girl took the scrap and rubbed it inside the pot, which was something her mother had always done to flavor the soup. Privately, the girl felt that it was like hoping a boiled saddle might taste like meat. She untied her skirt, retied it around the mouth of the pot, and splashed in water from the bucket. Then she scraped the circle of mud off the skirt and put it back on. Her skirt was no dirtier than before, and at least the water was clean.

She was lighting the fire when her father came by. She observed him from inside the lean-to. He was one of those people who has eyes that look like eyes, and a nose like a nose. Non- descript. Starvation had pulled the skin tight over his face until it was one plane from cheekbone to chin, and another from one corner of his chin to the other. Now and then the girl wondered if her father was actually a young man, or at least not a very old one. It was hard to tell.

Her father was carrying a winter melon under his arm. It was small, the size of a newborn baby, and its powdery white skin was dusty from having been buried underground for nearly two years. The tender look on her father’s face surprised the girl. She had never seen that expression on him before, but she knew what it meant. That was their last melon.

Her father squatted next to the flat-topped stump where they had killed chickens and placed the melon on it like an offering to the ancestors. He hesitated, cleaver in hand. The girl knew what he was thinking. A cut melon didn’t keep. She felt a rush of mixed emotions. For a few glorious days they would have food. A memory boiled up: soup made with pork bones and salt, the surface swimming with droplets of golden oil. The al- most gelatinous flesh of the melon, as translucent as the eye of a fish, yielding sweetly between her teeth. But once the melon was done, there would be nothing except the yellow beans. And after the yellow beans, there would be nothing.

The cleaver smacked down, and after a moment the girl’s father came in. When he handed her the chunk of melon, his tender look was gone. “Cook it,” he said shortly, and left.

The girl peeled the melon and cut the hard white flesh into pieces. She had forgotten melon smell: candle wax, and an elm-blossom greenness. For a moment she was gripped by the desire to shove it in her mouth. Flesh, seeds, even the sharp peel, all of it stimulating every inch of her tongue with the glorious ecstasy of eating. She swallowed hard. She knew her worth in her father’s eyes, and the risk that a theft would bring. Not all the girls who died had starved. Regretfully, she put the melon into the pot with a scatter of yellow beans. She cooked it for as long as the wood lasted, then took the folded pieces of bark she used as pot holders and carried the food into the house.

Chongba looked up from where he was sitting on the bare floor next to their father. Unlike his father, his face provoked comment. He had a pugnacious jaw and a brow as lumpy as a walnut. These features made him so strikingly ugly that the onlooker’s eye found itself caught in unwitting fascination. Now Chongba took the spoon from the girl and served their fa- ther. “Ba, please eat.” Then he served himself, and finally the girl.

The girl examined her bowl and found only beans and water. She returned her silent stare to her brother. He was already eating and didn’t notice. She watched him spoon a chunk of melon into his mouth. There was no cruelty in his face, only blind, blissful satisfaction: that of someone perfectly concerned with himself. The girl knew that fathers and sons made the pattern of the family, as the family made the pattern of the universe, and for all her wishful thinking she had never really expected to be allowed to taste the melon. It still rankled. She took a spoonful of soup. Its path into her body felt as hot as a coal.

Chongba said with his mouth full, “Ba, we nearly got a rat today, but it got away.”

Remembering the boys beating on the stump, the girl thought scornfully: Nearly.

Chongba’s attention shifted to her. But if he was waiting for her to volunteer something, he could wait. After a moment he said directly, “I know you caught something. Give it to me.”

Keeping her gaze fixed on her bowl, the girl found the twitching packet of crickets in her pocket. She handed it over. The hot coal grew.

“That’s all, you useless girl?”

She looked up so sharply that he flinched. He’d started calling her that recently, imitating their father. Her stomach was as tight as a clenched fist. She let herself think of the lizard hidden in the kitchen. She would dry it and eat it in secret all by herself. And that would be enough. It had to be.

They finished in silence. As the girl licked her bowl clean, her father laid out two melon seeds on their crude family shrine: one to feed their ancestors, and the other to appease the wandering hungry ghosts who lacked their own descendants to remember them.

After a moment the girl’s father rose from his stiff reverence before the shrine. He turned back to the children and said with quiet ferocity, “One day soon our ancestors will intervene to end this suffering. They will.”

The girl knew he was right. He was older than her and knew more. But when she tried to imagine the future, she couldn’t. There was nothing in her imagination to replace the form- less, unchanging days of starvation. She clung to life because it seemed to have value, even if only to her. But when she thought about it, she had no idea why.

The girl and Chongba sat listlessly in their doorway, looking out. One meal a day wasn’t enough to fill anyone’s time. The heat was most unbearable in the late afternoon, when the sun slashed backhanded across the village, as red as the last native emperors’ Mandate of Heaven. After sunset the evenings were merely breathless. In the Zhu family’s part of the village the houses sat apart from one another, with a wide dirt road be- tween. There was no activity on the road or anywhere else in the falling dusk. Chongba fiddled with the Buddhist amulet he wore, and kicked at the dirt, and the girl gazed at the crescent moon where it edged above the shadow of the far hills.

Both children were surprised when their father came around the side of the house. There was a chunk of melon in his hand. The girl could smell the edge of spoil in it, though it had only been cut that morning.

“Do you know what day it is?” he asked Chongba.

It had been years since the peasants had celebrated any of the festivals that marked the various points of the calendar. After a while Chongba hazarded, “Mid-Autumn Festival?”

The girl scoffed privately: Did he not have eyes to see the moon?

“The second day of the ninth month,” her father said. “This is the day you were born, Zhu Chongba, in the year of the Pig.” He turned and started walking. “Come.”

Chongba scrambled after him. After a moment the girl followed. The houses along the road made darker shapes against the sky. She used to be scared of walking this road at night be- cause of all the feral dogs. But now the night was empty. Full of ghosts, the remaining villagers said, although since ghosts were as invisible as breath or qi, there was no telling if they were there or not. In the girl’s opinion, that made them of less concern: she was only scared of things she could actually see.

They turned from the main road and saw a pinprick of light ahead, no brighter than a random flash behind one’s eyelids. It was the fortune teller’s house. As they went inside, the girl realized why her father had cut the melon.

The first thing she saw was the candle. They were so rare in Zhongli that its radiance seemed magical. Its flame stood a hand high, swaying at the tip like an eel’s tail. Beautiful, but disturbing. In the girl’s own unlit house she had never had a sense of the dark outside. Here they were in a bubble sur- rounded by the dark, and the candle had stolen her ability to see what lay outside the light.

The girl had only ever seen the fortune teller at a distance before. Now, up close, she knew at once that her father was not old. The fortune teller was perhaps even old enough to re- member the time before the barbarian emperors. A mole on his wrinkled cheek sprouted a long black hair, twice as long as the wispy white hairs on his chin. The girl stared.

“Most worthy uncle.” Her father bowed and handed the melon to the fortune teller. “I bring you the eighth son of the Zhu family, Zhu Chongba, under the stars of his birth. Can you tell us his fate?” He pushed Chongba forward. The boy went eagerly.

The fortune teller took Chongba’s face between his old hands and turned it this way and that. He pressed his thumbs into the boy’s brow and cheeks, measured his eye sockets and nose, and felt the shape of his skull. Then he took the boy’s wrist and felt his pulse. His eyelids drooped and his expression became severe and internal, as if interpreting some distant message. A sweat broke out on his forehead.

The moment stretched. The candle flared and the blackness outside seemed to press closer. The girl’s skin crawled, even as her anticipation grew.

They all jumped when the fortune teller dropped Chongba’s arm. “Tell us, esteemed uncle,” the girl’s father urged.

The fortune teller looked up, startled. Trembling, he said, “This child has greatness in him. Oh, how clearly did I see it! His deeds will bring a hundred generations of pride to your fam- ily name.” To the girl’s astonishment he rose and hurried to kneel at her father’s feet. “To be rewarded with a son with a fate like this, you must have been virtuous indeed in your past lives. Sir, I am honored to know you.”

The girl’s father looked down at the old man, stunned. After a moment he said, “I remember the day that child was born. He was too weak to suck, so I walked all the way to Wuhuang Monastery to make an offering for his survival. A twenty-jin sack of yellow beans and three pumpkins. I even promised the monks that I would dedicate him to the monastery when he turned twelve, if he survived.” His voice cracked: desperate and joyous at the same time. “Everyone told me I was a fool.”

Greatness. It was the kind of word that didn’t belong in Zhongli. The girl had only ever heard it in her father’s stories of the past. Stories of that golden, tragic time before the barbarians came. A time of emperors and kings and generals; of war and betrayal and triumph. And now her ordinary brother, Zhu Chongba, was to be great. When she looked at Chongba, his ugly face was radiant. The wooden Buddhist amulet around his neck caught the candlelight and glowed gold, and made him a king.

As they left, the girl lingered on the threshold of the dark. Some impulse prompted her to glance back at the old man in his pool of candlelight. Then she went creeping back and folded herself down very small before him until her head was touching the dirt and her nostrils were full of the dead chalk smell of it. “Esteemed uncle. Will you tell me my fate?”

She was afraid to look up. The impulse that had driven her here, that hot coal in her stomach, had abandoned her. Her pulse rabbited. The pulse that contained the pattern of her fate. She thought of Chongba holding that great fate within him. What did it feel like, to carry that seed of potential? For a moment she wondered if she had a seed of potential within herself too, and it was only that she had never known what to look for; she had never had a name for it.

The fortune teller was silent. The girl felt a chill drift over her. Her body broke out in chicken-skin and she huddled lower, trying to get away from that dark touch of fear. The candle flame lashed.

Then, as if from a distance, she heard the fortune teller say: “Nothing.”

The girl felt a dull, deep pain. That was the seed within her, her fate, and she realized she had known it all along.

The days ground on. The Zhu family’s yellow beans were running low, the water was increasingly undrinkable, and the girl’s traps were catching less and less. Many of the remaining villagers set out on the hill road that led to the monastery and beyond, even though everyone knew it was just exchanging death by starvation for death by bandits. The girl’s father alone seemed to have found new strength. Every morning he stood outside under the rosy dome of that unblemished sky and said like a prayer, “The rains will come. All we need is patience, and faith in Heaven to deliver Zhu Chongba’s great fate.”

One morning the girl, sleeping in the depression she and Chongba had made for themselves next to the house, woke to a noise. It was startling: they had almost forgotten what life sounded like. When they went to the road they saw something even more surprising. Movement. Before they could think, it was already rushing past in a thunderous press of noise: men on filthy horses that flung up the dust with the violence of their passage.

When they were gone Chongba said, small and scared, “The army?”

The girl was silent. She wouldn’t have thought those men could have come from that dark flowing river, beautiful but al- ways distant.

Behind them, their father said, “Bandits.”

That afternoon three of the bandits came stooping under the Zhu family’s sagging lintel. To the girl, crouched on the bed with her brother, they seemed to fill the room with their size and rank smell. Their tattered clothes gaped and their untied hair was matted. They were the first people the girl had ever seen wearing boots.

The girl’s father had prepared for this event. Now he rose and approached the bandits, holding a clay jar. Whatever he felt, he kept it hidden. “Honored guests. This is only of the poorest quality, and we have but little, but please take what we have.”

One of the bandits took the jar and looked inside. He scoffed. “Uncle, why so stingy? This can’t be all you have.”

Their father stiffened. “I swear to you, it is. See for yourself how my children have no more flesh on them than a sick dog! We’ve been eating stones for a long time, my friend.”

The bandit laughed. “Ah, don’t bullshit me. How can it be stones if you’re all still alive?” With a cat’s lazy cruelty, he shoved the girl’s father and sent him stumbling. “You peasants are all the same. Offering us a chicken, expecting us not to see the fatted pig in the pantry! Go get the rest of it, you cunt.”

The girl’s father caught himself. Something changed in his face. In a surprising burst of speed he lunged at the children and caught the girl by the arm. She cried out in surprise as he dragged her off the bed. His grip was hard; he was hurting her.

Above her head, her father said, “Take this girl.”

For a moment the words didn’t make sense. Then they did. For all her family had called her useless, her father had finally found her best use: as something that could be spent to benefit those who mattered. The girl looked at the bandits in terror. What possible use could she have to them?

Echoing her thoughts, the bandit said scornfully, “That little black cricket? Better to give us one five years older, and prettier—” Then, as realization dawned, he broke off and started laughing. “Oh, uncle! So it’s true what you peasants will do when you’re really desperate.”

Dizzy with disbelief, the girl remembered what the village children had taken pleasure in whispering to one another. That in other, worse-off villages, neighbors would swap their youngest children to eat. The children had thrilled with fear, but none of them had actually believed it. It was only a story.

But now, seeing her father avoiding her gaze, the girl realized it wasn’t just a story. In a panic she began struggling, and felt her father’s hands clench tighter into her flesh, and then she was crying too hard to breathe. In that one terrible moment, she knew what her fate of nothing meant. She had thought it was only insignificance, that she would never be anything or do anything that mattered. But it wasn’t.

It was death.

As she writhed and cried and screamed, the bandit strode over and snatched her from her father. She screamed louder, and then thumped onto the bed hard enough that all her breath came out. The bandit had thrown her there.

Now he said, disgusted, “I want to eat, but I’m not going to touch that garbage,” and punched their father in the stomach. He doubled over with a wet squelch. The girl’s mouth opened silently. Beside her, Chongba cried out.

“There’s more here!” One of the other bandits was calling from the kitchen. “He buried it.”

Their father crumpled to the floor. The bandit kicked him under the ribs. “You think you can fool us, you lying son of a turtle? I bet you have even more, hidden all over the place.” He kicked him again, then again. “Where is it?”

The girl realized her breath had come back: she and Chongba were both shrieking for the bandit to stop. Each thud of boots on flesh pierced her with anguish, the pain as intense as if it were her own body. For all her father had shown her how little she meant to him, he was still her father. The debt children owed their parents was incalculable; it could never be repaid. She screamed, “There isn’t any more! Please stop. There isn’t. There isn’t—”

The bandit kicked their father a few more times, then stopped. Somehow the girl knew it hadn’t had anything to do with their pleading. Their father lay motionless on the ground. The bandit crouched and lifted his head by the topknot, revealing the bloodied froth on the lips and the pallor of the face. He made a sound of disgust and let it drop.

The other two bandits came back with the second jar of beans. “Boss, looks like this is it.”

“Fuck, two jars? I guess they really were going to starve.” After a moment the leader shrugged and went out. The other two followed.

The girl and Chongba, clinging to each other in terror and exhaustion, stared at their father where he lay on the churned dirt. His bloodied body was curled up as tightly as a child in the womb: he had left the world already prepared for his reincarnation.

That night was long and filled with nightmares. Waking up was worse. The girl lay on the bed looking at her father’s body. Her fate was nothing, and it was her father who would have made it happen, but now it was he who was nothing. Even as she shuddered with guilt, she knew it hadn’t changed anything. Without their father, without food, the nothing fate still awaited.

She looked over at Chongba and startled. His eyes were open, but fixed unseeing on the thatched roof. He barely seemed to breathe. For a horrible instant the girl thought he might be dead as well, but when she shook him he gave a small gasp and blinked. The girl belatedly remembered that he couldn’t die, since he could hardly become great if he did. Even with that knowledge, being in that room with the shells of two people, one alive and one dead, was the most frighteningly lonely thing the girl had ever experienced. She had been surrounded by people her whole life. She had never imagined what it would be like to be alone.

It should have been Chongba to perform their last filial duty. Instead, the girl took her father’s dead hands and dragged the body outside. He had withered so much that she could just manage. She laid him flat on the yellow earth behind the house, took up his hoe, and dug.

The sun rose and baked the land and the girl and everything else under it. The girl’s digging was only the slow, scraping erosion of layers of dust, like the action of a river over the centuries. The shadows shortened and lengthened again; the grave deepened with its infinitesimal slowness. The girl gradually became aware of being hungry and thirsty. Leaving the grave, she found some muddy water in the bucket. She scooped it with her hands and drank. She ate the meat for rubbing the pot, recoiling at its dark taste, then went into the house and looked for a long time at the two dried melon seeds on the ancestral shrine. She remembered what people had said would happen if you ate a ghost offering: the ghosts would come for you, and their anger would make you sicken and die. But was that true? The girl had never heard of it happening to anyone in the village—and if no one could see ghosts, how could they be sure what ghosts did? She stood there in an agony of indecision. Finally she left the seeds where they were and went out- side, where she grubbed around in last year’s peanut patch and found a few woody shoots.

After she had eaten half the shoots, the girl looked at the other half and deliberated on whether to give them to Chongba, or to trust in Heaven to provide for him. Eventually guilt prodded her to go wave the peanut shoots over his face. Something in him flared at the sight. For a moment she saw him struggling back to life, fueled by that king-like indignation that she should have given him everything. Then the spark died. The girl watched his eyes drift out of focus. She didn’t know what it meant, that he would lie there without eating and drinking. She went back outside and kept digging.

When the sun set the grave was only knee deep, the same clear yellow color at the top as it was at the bottom. The girl could believe it was like that all the way down to the spirits’ home in the Yellow Springs. She climbed into bed next to Chongba’s rigid form and slept. In the morning, his eyes were still open. She wasn’t sure if he had slept and woken early, or if he had been like that all night. When she shook him this time, he breathed more quickly. But even that seemed reflexive.

She dug again all that day, stopping only for water and pea- nut sprouts. And still Chongba lay there, and showed no interest when she brought him water.

She awoke before dawn on the morning of the third day. A sense of aloneness gripped her, vaster than anything she had ever felt. Beside her, the bed was empty: Chongba had gone.

She found him outside. In the moonlight he was a pale blur next to the mass that had been their father. At first she thought he was asleep. Even when she knelt and touched him it took her a long time to realize what had happened, because it didn’t make any sense. Chongba was to have been great; he was to have brought pride to their family name. But he was dead.

The girl was startled by her own anger. Heaven had promised Chongba life enough to achieve greatness, and he had given up that life as easily as breathing. He had chosen to become nothing. The girl wanted to scream at him. Her fate had always been nothing. She had never had a choice.

She had been kneeling there for a long time before she noticed the glimmer at Chongba’s neck. The Buddhist amulet. The girl remembered the story of how her father had gone to Wuhuang Monastery to pray for Chongba’s survival, and the promise he had made: that if Chongba survived, he would re- turn to the monastery to be made a monk.

A monastery—where there would be food and shelter and protection.

She felt a stirring at the thought. An awareness of her own life, inside her: that fragile, mysteriously valuable thing that she had clung to so stubbornly throughout everything. She couldn’t imagine giving it up, or how Chongba could have found that option more bearable than continuing. Becoming nothing was the most terrifying thing she could think of— worse even than the fear of hunger, or pain, or any other suffering that could possibly arise from life.

She reached out and touched the amulet. Chongba had be- come nothing. If he took my fate and died . . . then perhaps I can take his, and live.

Her worst fear might be of becoming nothing, but that didn’t stop her from being afraid of what might lie ahead. Her hands shook so badly that it took her a long time to undress the corpse. She took off her skirt and put on Chongba’s knee-length robe and trousers; untied her hair buns so her hair fell loose like a boy’s; and finally took the amulet from his throat and fastened it around her own.

When she finished she rose and pushed the two bodies into the grave. The father embracing the son to the last. It was hard to cover them; the yellow earth floated out of the grave and made shining clouds under the moon. The girl laid her hoe down. She straightened—then recoiled with horror as her eyes fell upon the two motionless figures on the other side of the filled grave.

It could have been them, alive again. Her father and brother standing in the moonlight. But as instinctively as a new- hatched bird knows a fox, she recognized the terrible presence of something that didn’t—couldn’t—belong to the ordinary hu- man world. Her body shrank and flooded with fear, as she saw the dead.

The ghosts of her father and brother were different from how they had been when alive. Their brown skin had grown pale and powdery, as if brushed with ashes, and they wore rags of bleached-bone white. Instead of being bound in its usual top- knot, her father’s hair hung tangled over his shoulders. The ghosts didn’t move; their feet didn’t quite touch the ground. Their empty eyes gazed at nothing. A wordless, incomprehensible murmur issued from between their fixed lips.

The girl stared, paralyzed with terror. It had been a hot day, but all the warmth and life in her seemed to drain away in response to the ghosts’ emanating chill. She was reminded of the dark, cold touch of nothingness she had felt when she had heard her fate. Her teeth clicked as she shivered. What did it mean, to suddenly see the dead? Was it a Heavenly reminder of the nothingness that was all she should be?

She trembled as she wrenched her eyes from the ghosts to where the road lay hidden in the shadow of the hills. She had never imagined leaving Zhongli. But it was Zhu Chongba’s fate to leave. It was his fate to survive.

The chill in the air increased. The girl startled at the touch of something cold, but real. A gentle, pliant strike against her skin—a sensation she had forgotten long ago, and recognized now with the haziness of a dream.

Leaving the blank-eyed ghosts murmuring in the rain, she walked.

The girl came to Wuhuang Monastery on a rainy morning. She found a stone city floating in the clouds, the glazed curves of its green-tiled roofs catching the light far above. Its gates were shut. It was then that the girl learned a peasant’s long-ago promise meant nothing. She was just one of a flood of desperate boys massed before the monastery gate, pleading and crying for admittance. That afternoon, monks in cloud-gray robes emerged and screamed at them to leave. The boys who had been there overnight, and those who had already realized the futility of waiting, staggered away. The monks retreated, taking the bodies of those who had died, and the gates shut behind them.

The girl alone stayed, her forehead bent to the cold monastery stone. One night, then two and then three, through the rain and the increasing cold. She drifted. Now and then, when she wasn’t sure whether she was awake or dreaming, she thought she saw chalky bare feet passing through the edges of her vision. In more lucid moments, when the suffering was at its worst, she thought of her brother. Had he lived, Chongba would have come to Wuhuang; he would have waited as she was waiting. And if this was a trial Chongba could have survived— weak, pampered Chongba, who had given up on life at its first terror—then so could she.

The monks, noticing the child who persisted, doubled their campaign against her. When their screaming failed, they cursed her; when their cursing failed, they beat her. She bore it all. Her body had become a barnacle’s shell, anchoring her to the stone, to life. She stayed. It was all she had left in her to do.

On the fourth afternoon a new monk emerged and stood over the girl. This monk wore a red robe with gold embroidery on the seams and hem, and an air of authority. Though not an old man, his jowls drooped. There was no benevolence in his sharp gaze, but something else the girl distantly recognized: interest.

“Damn, little brother, you’re stubborn,” the monk said in a tone of grudging admiration. “Who are you?”

She had kneeled there for four days, eating nothing, drinking only rainwater. Now she reached for her very last strength. And the boy who had been the Zhu family’s second daughter said, clearly enough for Heaven to hear, “My name is Zhu Chongba.”

She Who Became The Sun by Shelley Parker-Chan is out in hardback with Mantle Books on 22 July 2021. Click here to read our full interview with Shelley, who you can follow at @shelleypchan.