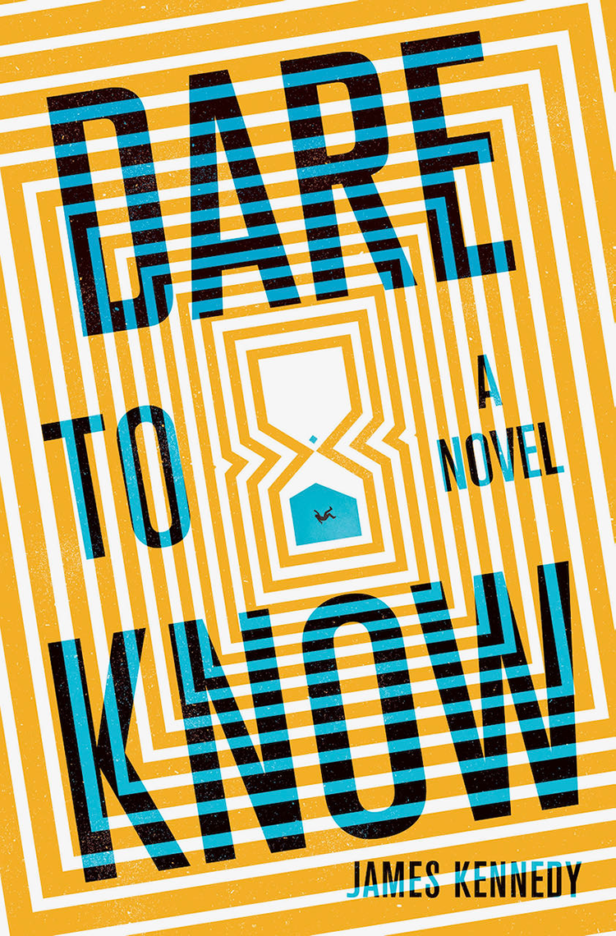

James Kennedy’s Dare To Know is mind-bending and emotional speculative thriller set in a world where the exact moment of your death can be predicted – for a price.

Our narrator is the most talented salesman and death predictor at the prestigious company Dare to Know. Though he’s mastered the art of death, the rest of his life is a failure, driving him to violate the cardinal rule of his business —forecasting his own death. The problem: apparently, he died 23 minutes ago.

The only person who can confirm its accuracy is Julia, the woman he loved and lost during his rise up the ranks of Dare to Know. As he travels across the country to see her, he’s forced to confront his past, the choices he’s made, and the terrifying truth about the company he works for…

We still have to wait a while until Dare To Know is released this September but if you’re like us and can’t wait to get lost in James Kennedy’s intense world, here is an exclusive extract…

I have death in my pocket. Folded up, ready to go. Ordinarily I wouldn’t take on a client like this, but I have to make this sale.

Driving up 290 through gray December slush to Starbucks.My own office is long gone. Now I’ve got to do business at a cruddy table for two—not ideal, but three bucks for coffee beats thousands of dollars a month on rent, upkeep, a secretary . . . did I really used to have a secretary? What’d she even do? In any case, the margins aren’t there anymore. Took a while for me to understand that. Reality is, this is no longer a classy business.

I’d done the initial calculation in advance. Checked it again. Stuck it in my wallet. I need this to go smoothly.

Once upon a time, this business was strictly referral. We’d pick and choose. Ads? Please. We wouldn’t even give you a follow-up meeting if we pegged you as obnoxious or, worse, “delicate”—because we weren’t just salespeople; we had to be on-the-spot therapists too. Had to handle the client’s reaction. Got special training for that, way back when. Unpredictable, the way the client would take it. You might tell some successful pillar of society “thirty-one years” and he’d freak out and spiral into a nervous breakdown right in front of you. Whereas to some loser you might say “two years” and he’d actually shape up, get his life in order. Finding out was the smartest move he’d ever made.

I developed an eye for it. Could sense how someone would react. Got consulted on hard cases. No sale’s worth a meltdown. It’s bad for business, that’s why management gave us discretion back then. I mean the old management, Blattner and Hansen, before they cashed out. Anyway, I’d make my judgment. Jack up the price if my client wasn’t taking it seriously. Raise it until they did. But cut them a discount, too, if I sensed the need. Not purely out of altruism. If customers are running around bitching they wish we’d never told them, that’s bad PR. But those times when it worked out—we loved those inspiring stories. Or marketing did.

We could afford to turn away business back then, back when the calculations could take several days to complete and we charged upwards of twenty million a pop. Now any joker who can scrape up twenty grand can get their answer in an hour. And believe me, if I don’t jump on that sale, Martin McNiff will. So even when I’m at some dingy food court, looking in a client’s eyes, and I know that when I say “three years,” it’ll destroy her, I think of alimony, college for the boys, the condo, this joke of a car—I just need that shitty fifteen percent.

Parking at Starbucks, I shut off the engine. Sit there a minute. Drizzle flecks the windshield. Not even four o’clock and it’s already dark. Never thought I’d end up here, right where I started. Always thought I’d make it out to California or something. Julia did.

Put my game face on. We used to give it a sense of occasion. Called it the Moment. I still prefer to give it a sense of occasion. Not pretentious, just basic self-respect, respect for the client, respect for what I’m selling. It’s part of the service. Outdated philosophy, I know. Still, it doesn’t feel right to me, to tell my client in this mini- mall coffee shop, barely a step up from a McDonald’s. Here’s what surprises me, though: clients don’t care. Some actually complain: “why can’t you just tell me over the phone”—well, Martin McNiff will tell you over the phone, sure. He’ll even text it to you. But I don’t. Look, I get it. I’m old-fashioned.

When you have your Moment, there should be a sense of occasion.

So many treat it like it’s no big deal now. I’ve had clients actually call up their friends as soon as they find out. Blabbing it in a lighthearted, isn’t-it-funny way. That’s the worst. When they joke about it. Baffles me. Back when I was starting out you’d actually get to see the client’s face change in front of your eyes. Disbelief. Terror. Relief. Hopelessness. Something. Now: nothing. Like I’m giving them a quote for drywall.

When we started out, when we were still Sapere Aude, it was hard for us to get taken seriously. But one hundred percent accuracy makes the skeptics shut up.

It was most satisfying when the skeptics shut up permanently. On precisely the time and date we predicted.

Nowadays I keep the prediction books in my car. They look like a bunch of phone directories, cheap paper packed with columns of tiny type. I keep them in the trunk along with a couple of pressed shirts and an extra suit. With no office, I have to lug the books around everywhere, but the thing is, I can’t help but feel that having these books with me all the time, instead of on a proper bookshelf, makes the whole enterprise feel low rent.

We used to keep the books in a special room at the office. People mock that now, I know. But still, I kind of miss it. Back then the books were leather bound with sheepskin paper. Beautiful fonts. Medieval-style illuminations, even. We’d bring them out with a kind of reverence. Not grandiose, just an unfussy recognition of the seriousness of what was about to occur. Like a sacrament. A priest doesn’t freak out every time he makes bread turn into God. It’s just his job. He’s a professional.

To do the math makes the math come true.

So we’d unlock the glass case and bring out the books. People always wanted to peek at what was on the pages. We showed them because why not? To anyone except a trained professional it’s incomprehensible anyway, just endless, closely spaced columns of tiny numbers and symbols, like a phone book translated into cuneiform got infected with calculus and then mated with the Egyptian Book of the Dead. That’s what we nicknamed them: the Books of the Dead.

After the client gawked at the books, we’d get down to business. Leaf through the pages, cross-reference the client’s info, ask the questions, do a calculation, flip back and forth through the different volumes, more questions, more calculations, closing in on a number—until I would actually feel the number, like I could physically sense the number drawing closer to me, until it were almost trembling in my hand. This was the Moment; this was the Moment that made a professional.

Because you don’t just blurt it out.

It takes tact, sensitivity.

Different people want a different kind of person to tell them.

Blattner and Hansen figured that out early on. Some folks want a trustworthy older banker type. In that case they’d send you to Hutchinson. If you preferred to keep the information at an ironic arm’s length, if you wanted to find out just for a lark (early on that was most of our clientele), they’d send you to Ziegler. If you wanted a pretty woman to tell you, they’d send you to Julia. Part of Blattner and Hansen’s old-school cluelessness was that they’d only hired one woman at first. The sexy sell, right? Of course Julia knew her shit, as we all did, but there’s no denying that a certain type of rich asshole would rather be told by a redhead who would maybe, oh just maybe, let him cry on her shoulder. That was Blattner and Hansen’s angle, anyway. Once they saw Julia’s numbers, though, they woke up. More women got hired.

But none of them were quite like Julia.

Me, I got the skeptics. The engineers, the professors, the cynics, people who wanted it all clearly explained. I was their man. Starting out, I was the only one in sales who even had a proper scientific background, though for all my reputation, no, I wasn’t really a working scientist. Abandoned my physics doctorate to take this job, don’t get me started. Still, I could explain the way it worked, or as far as the clients’ understanding would go.

We were the first ones. The pioneers. But so what? You can’t keep the fundamental science secret. What we were doing with thanatons, it’s not magic, though when it’s first explained to you, sure, it certainly sounds like magic. So does quantum theory, right? I was amused at the objections to the process at first. “It doesn’t make sense that you have to calculate everything with a pencil and paper. Can’t you have a computer do it?”

As if that were the weirdest thing about thanatons.

In any case, the computer inevitably fucks up somewhere. On a theoretical level I can demonstrate to you, step by step, why the computer must fuck up—how the calculation can’t help but go off the rails if it’s performed purely mechanically—but would that really help you? I had to study thanaton theory for years for a reason. No shortcuts. Suffice it to say that something irreplaceable is generated in the give-and-take between the client and me, the interview and the calculations, as we work through each step of the algorithm together. Something that swings the result, makes it correct. Crazy, yeah. But no crazier than Schrödinger’s cat, both alive and dead at once.

The upshot: shut up and calculate.

And as for the thanaton of thanatons—the eschaton—

Shut up and calculate.

Still, I should’ve seen it coming. Me of all people. Because soon enough, other companies also solved the engineering puzzle of how to tease information out of thanatons (or, as the media dubbed them, “death particles”). We could file all the patent infringement suits we liked but competitors flooded the market. Made it cheap, easy to access. What started out as a sublime privilege for millionaires became an upper-middle-class luxury. Then slipped into being a middle-class necessity. Now it’s a stupid curiosity for any schlub who doesn’t mind credit card debt. Downmarket. No sense of occasion. We ditched Sapere Aude—people didn’t get the reference, and it turned clients off. Rebranded the whole thing. Now we’re just Dare to Know.

Like I said: not classy anymore.

But I’ve got to make this sale.

The lady who’ll meet me at this Starbucks today, she’s my only promising lead. Truth is, I’m on the ropes. Martin McNiff is eating my lunch—isn’t that how an over-the-hill salesman like me would phrase it? Sure, whatever, I’m forty-nine, I admit it, I can’t hustle the way a twenty-eight-year-old can. And in some law-of-the-jungle corner of my mind, I accept this, I agree that Martin McNiff should be eating my lunch, I acknowledge the old must step aside and make way for the young, that I’ve had my chance, etc., etc. A sage perspective, maybe, but that doesn’t change the fact that I need the money.

Things seemed unlimited when I was young. To the point that I felt that I stayed objectively young for longer than other people, that I kept my freshness, my promise longer than them. Like I stayed parked at twenty-eight years old for fifteen years. I’d see friends from high school, college—they aged early, they seemed forty-five when they were only thirty, they lost their hair, got fat, dressed like shit, and it was hard for me not to suspect that it was their fault, that they’d made some obscure mistake that triggered the aging process. A mistake I’d somehow avoided. Wishful thinking. Still, the idea seeped into me. Turned into an unexamined principle upon which I based my life.

Until recently, the facts were on my side. Way into my thirties I seemed like I was still in my twenties, with a flat belly, plenty of hair, and a quick mind. But then of course I lost it, one day I woke up and I realized it was all gone, that it had been gone for years. I wasn’t a young go-getter. I was a corny uncle.

And now the Martin McNiffs are coming.

Martin McNiff works for one of the new start-ups. Companies that tell you not only when you’ll die but also how you’ll die.

It’s like high school physics, Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle— the idea that the more accurately you determine a particle’s position the less you can know that particle’s momentum, and vice versa, right?

That’s how McNiff’s system works. Except instead of measuring the position and momentum of a particle, he’s measuring the when and the how of your death. And the more accurately he can tell you one, the less accurately he can tell you the other.

Well, I can tell you this: Martin McNiff uses hack algorithms. My algorithms? The precision of a geometrical proof. Bulletproof like Euclid, one hundred percent. Martin McNiff—he’s got heuristics, he’s got rules of thumb, he’s got glorified actuarial tables, but he’s no scientist, he’s no artist. Though sonofabitch is fast, and yeah, he’s cheap.

But even McNiff will admit that if he sells you solely when you’ll die, or solely how you’ll die, his algorithm degrades. McNiff can only hit 88% accuracy max. That’s my in. That’s what I remind clients about. McNiff hustles statistics. I provide certainty. We all know that we’ll die someday. When I tell you exactly when that someday is, I’m relieving anxiety. Right?

Wrong. Turns out that’s not what clients want. Not really. People like their range narrowed down thrillingly, but they also like to keep that wiggle room at the end. And the addition of the “how you die”—McNiff’s twist—it’s clever.

But come on: if McNiff tells you that you have a 67.2% chance of dying by drowning on June tenth next year, and a 10.8% chance of dying of cancer on September fifth five years from now, etc., etc., I’d argue that you’re still always wondering which of those half dozen ways or days you’re going to bite the dust. And so even though Martin McNiff is eating my lunch (which he is, brutally), I’d argue the extra “information” McNiff gives you only leads to more anxiety—but, well, try explaining that to a client. It’s too many dots to connect and you can see where that pitch is going, i.e., straight into the toilet.

Long story short: Martin McNiff is eating my lunch.

I met him at a party once. McNiff. He joked that if there came along a company that told you not just when you died, and how you died, but also why you died, it’d drive us both out of business. “The philosophical why, I mean,” McNiff said, smiling, and by this point I didn’t know if it was a good-natured joke or if he was slipping the knife. I didn’t know how much McNiff knew about me personally. That’s the thing about being on the ropes: you second- guess yourself; you suspect everyone else; you don’t want to be a prick that can’t take a joke; but then again you don’t want to be the chump that anyone can mock; you lose your instincts; you laugh vaguely and change the subject; subtext becomes opaque; you can’t banter; in short, you’re a bore.

I get out of the car and hustle across the rainy, slushy parking lot. No umbrella, of course. Why didn’t I think ahead this morning? Rookie mistake. I’m going to look all bedraggled and damp. Nobody wants to hear the information from a wet, disheveled, middle-aged man. That’s what Ron Wolper would say, Ron Wolper who’s ten years younger than me, Ron Wolper who’s been breathing down my neck for the past year since I haven’t been able to make quota. Ron Wolper, one of the new hard-asses who came in when Sapere Aude was restructured into Dare to Know. Blattner and Hansen wouldn’t treat me this way. Blattner and Hansen wouldn’t say make quota this month or it’s my job. They’d let a couple of months slide.

Not Ron Wolper.

I’m early. I have fifteen minutes to go to the men’s room, fix myself up, find a table, get everything composed.

When I’d opened the book at lunch to do the preliminary calculation, crammed in the back seat, eating a drive-thru cheeseburger, I felt that familiar tug we all feel, that everyone in sales must resist: What if I looked myself up?

But of course that’s the taboo. That’s what you must never do. It would be impossible ever to do your job again, we were warned, if you knew the time of your own death. The number would inevitably loom too large in your mind, would disrupt your client’s calculation . . . Anyway, it’s technically theft, unless you intend to pay for the service of knowing when you’ll die, which, guess what, I can’t afford. Twenty thousand on credit? Guess again. The humiliating truth is my clients can afford this service and I can’t. Don’t think they can’t sniff that out, either. And the minute they know you need the sale, you’re sunk.

So dress like you don’t need the sale. Negotiate like you don’t need the sale. Hard to pull off when they see my car. When we’re meeting at a coffee shop. When I’m still wet from the fricking rain.

No umbrella. Jesus.

I broke up with Julia at a Starbucks just like this, like a shithead. She was moving to Bloomington and wanted me to come with her. I was in line to move up at Sapere Aude. If I stuck it out in Chicago one more year, Blattner and Hansen hinted, there was a good chance that I’d be promoted to the head office in San Francisco. I wasn’t about to sabotage my career by running off with her to Bloomington. I actually said to her, like a dick, “Who moves to Bloomington? Bloomington is a place you move from.” So I dumped her in a coffee shop just like this one, and bang, these coffee shops began popping up on every street corner, until in no time at all the country was blanketed with identical memorials to how I was a shitty twenty-five-year-old who couldn’t take his head out of his ass long enough to move to Bloomington and be happy with someone who loved him.

Julia lives in San Francisco now.

I’m still in Chicago.

Forget it. Make this sale.

I come into the Starbucks lugging my case full of Books of the Dead. I scan the tables. People tapping on their laptops, checking their phones.

The nausea. The cloud of sickness clinging around each glowing screen. Not as bad as sometimes. I can deal with it. Even still, I take a roundabout route through the tables. Buzzing static in my guts. No need to make it worse.

Multicolored string lights in the windows. Christmas carols playing. Candy cane decorations. Lisa Beagleman’s not here yet. Good. I brought my fresh suit out of my car, too, because I’d been taking meetings all over suburban Chicago nonstop in these wrinkled clothes since seven this morning. I looked rough. What I needed: fresh-pressed suit, ironed shirt, quick shoeshine, get my hair in order. In a negotiation, these things matter. It’s when I’m changing (in the men’s room, in the big handicapped stall, with my suit on the hook on the back of the door, hopping around on the pissy floor in my black socks, getting into new trousers) that my phone buzzes. It’s Erin.

Buzzing head static.

Just to be clear, I don’t hate Erin. The guys who, when I go out drinking, refer to their ex-wives as that bitch, implicitly inviting me to speak that way about Erin—I don’t respond in kind. It wasn’t a “good” divorce, but why hate her? Hating Erin would erase the good years when we were starting out, when the boys were young. I can’t help but feel those good times still exist, that those previous versions of Erin and me continue to inhabit a real location in space- time. I don’t want to deny or dishonor what was, probably, maybe, one of the better times of my life, or better than I’ll ever manage again. In short, Erin is not that bitch.

I touch my phone. Brace myself for the sick. Everyone who works with thanatons eventually gets this feeling, this queasy sensation around computers. And of course your phone’s just another computer. In the old office we had workarounds. We actually installed analog rotary-dial phones, Bakelite antiques with copper wiring. Good luck finding those nowadays. But how ridiculous is it to be a salesman who can barely use a phone or email? That’s why we used to have secretaries, of course. Computers feel like nails on a chalkboard when we walk in a room, the way they calculate creates a repellent aura—no matter how sleek the interface, how stylish the design, their math stinks up the room. Jabbing, stabbing, primitive, brutal.

I answer the phone, all business. That’s the deadening thing. Erin has to rearrange her work schedule and wants to know, can I take the boys this weekend instead of next? I can. Our voices, which used to be ecstatic together, or laughing together, or furious at each other, are now just working out scheduling details. In a way, ordinary conversations like this debase the old memories more thoroughly than if I had complained about that bitch.

The boys, sure, I care about them, but by some genetic fluke, both of them look and act just like Erin’s lunkheaded brother Bryce. Go ahead, admit it. Bryce’s DNA dominated mine. As the years go by, and especially since the divorce, I have less and less in common with the boys. Stopped recommending books to them. They don’t read anyway. They gave up trying to talk to me about sports. I never cared about sports, there’s no point in faking it now. So yeah, I’m disengaged from my sons’ lives. Yeah, I should make more of an effort. I try to reengage, but I don’t know how. I see myself fading in their eyes.

I hang up. The phone’s algorithms calm down. Put it in my pocket. The queasiness clinging to the thing ebbs. My stomach relaxes.

I come out of the bathroom, buy a coffee to justify my existence, and take the table near the window.

It’s only once I’m settled in that I see that Lisa Beagleman is already there.

In fact, I realize, Lisa Beagleman had been there all along. I must’ve walked straight past her on my way to the bathroom. There, in the corner—a large sour-looking woman in a gray sweatshirt, off-brand jeans, and squinting, distrustful eyes. Well, I’m no prize either. I should’ve recognized her but her nothing-colored hair was in a ponytail last time. Never could remember a face.

I am here to tell Lisa Beagleman when she will die.

She looks up at me from her table and I understand, right away, that this sale isn’t going to go the way I want. She smiles at me and it’s a predatory, stupid smile.

“Freshening up?” she says as I sit down at her table.

“Thanks for being patient.” Off on the wrong foot; she has the upper hand already. She knows it. How to play it? Lighthearted. “And here I thought I was early.”

“You still are.” Lisa Beagleman makes it sound like an accusation. I check my watch: yes, I’m still six minutes early. Her smile says it all. You really need this.

“Before we start, just to confirm—” I make a show of going through some papers but who am I fooling? I produce the invoice. “If you can sign off on this and a few more pieces of paperwork . . .”

She doesn’t even look at the invoice. “Well, the thing is, I just got off the phone with Martin McNiff—you know, Martin McNiff?”

Don’t take the bait. “Uh-huh.”

“And after talking to him, well, I just don’t know about twenty thousand dollars.” Seriously, even the littlest things about Lisa Beagleman are irritating, like why’d she put that meaningless emphasis on the word “dollars”? She’d prefer to pay in what, Krugerrands?

Shut up. Let her talk.

“You know?” Lisa gives a put-upon sigh. That nasal, wheedling voice. Quacking her midwestern vowels. “It’s just that for twelve thousand dollars Martin McNiff said he could tell me both when and how, and I thought, here I am with you, spending twenty thousand on just when.”

Is Lisa Beagleman for real? Does she really want me to explain it all over again? How I provide certainty while McNiff can only give her statistics? I’d explained it to her on the phone. I’d mailed her the brochures. Well, I’m not going round and round on this. Nickel- and-dimed by a Lisa Beagleman. Christ.

I let the silence sit there.

“You know?” she says.

Hardball. “I’m sorry to hear that. I suppose you must’ve gotten off the phone with Mr. McNiff just now, or else you would’ve canceled our appointment and notified me sooner.” I gather my papers and rise. “I’ll let you go then—”

A lie. But it works. I see it in her eyes. She’d overplayed her hand.

“No, calm down, sit down,” she says. Trying to regain the initiative by implying I’m overreacting. Telling me to sit down is giving me an order. Putting me in my place. Obviously a dim bulb, but she might be a savant at small-time wheedling. Everyone’s good at something.

I don’t sit down. “Twenty thousand.”

“Okay, okay, okay,” she says, which isn’t an agreement but I sit down anyway.

—0—

She got me down to sixteen thousand.

Is it a smell that I give off? Some chump pheromone? It can’t have always been the case. I used to close multimillion-dollar deals. Must be like the invisible desperation you emanate when you haven’t been laid yet. Only when someone finally fucks you does the stink vanish. But still, even after that, fail too many times, accept too many nights alone, that stink sneaks back. Deep down I don’t really believe I’m a loser, although for the last few years the world’s been informing me otherwise. My problem is I don’t listen. I keep expecting everything will turn my way.

Fifteen percent of sixteen thousand is twenty-four hundred, I’m thinking, as I start in on the standard introductory spiel for the millionth time. She’s almost certainly already seen actors recite this spiel on TV; by now it’s as ingrained in pop culture as the reading of Miranda rights.

“I’m going to say some sentences that will seem like nonsense,” I begin. “I’d like you to respond to each sentence with the first words that come into your head, no matter how seemingly odd or random. Please don’t try to be clever or funny. Please don’t try to beat the system. The algorithm has taken those possible responses into account and it will only result in a longer session. None of the statements touch upon conscious personal information, and the responses we aim to elicit from you will also have no conscious personal content.”

“Yeah, yeah,” says Lisa Beagleman.

Spiel over. I initiate the stage one calculation I’d calibrated for her in the car. “Blue lady lays, a wending way around away, eels conceal the puck.”

“Oh come on,” she says impatiently. “It really does work like this?”

I make a note in my book. “Marry fluorescent chatter, romping willowy hunger flash.”

“So stupid. Beep bop boop. I don’t know.”

Another note. “Ornery ourobouros, kill sky love shield, raw throat lizard eyes.”

Lisa Beagleman just shakes her head.

I put my pen aside. Just use the scripted response here. I don’t have the energy to meet this woman on her own terms.

“I’m going to pause the assessment,” I recite, “and remind you that you voluntarily asked for this information, were fully briefed on the process, and already paid your deposit. When we complete the assessment, I will be able to predict the date and time of your death to an accuracy of one hundred percent. If you continue to resist the questions, that will only make the assessment longer.”

Challenging eyes. “And what if I don’t want to know now?”

“That’s perfectly okay if you don’t want to know anymore,” I lie. “But you’ve already paid your ten percent deposit, and that’s nonrefundable.”

I don’t mention to Lisa Beagleman that if she quit now, I only get a reduced five percent of that ten percent. My full fifteen percent only kicks in if she goes all the way, finds out when she’ll die, and coughs up the full twenty thousand—strike that, sixteen thousand. Bottom line: if she walks away now, I’d only be netting . . . Jesus, eighty bucks.

I have to, have to close this thing.

“Quintile merryman main bus undervolt,” I say. Lisa Beagleman wavers, then: “Hawaii.”

—0—

Once I get them in rhythm, I’m good at keeping them locked in. “Salt hum winter cream,” I say.

“Treat aunt cottage door,” she says.

Time flies. I’m in the zone. After every exchange of seeming gibberish I consult the books, make the necessary calculation, derive the next words to say, then it all starts over again, faster, until we’re just jabbering letters and numbers at each other—“D 4 T G 8 9,” I say, and Lisa Beagleman rattles off “X 4 2 9 X 3 E”— and the thing is, I’m good at this, I enjoy it. Even though nowadays the assessment is standardized to the point where you don’t even have to be a real mathematician anymore—any technician can just execute the script—I get results faster using the original methods, plus a few custom shortcuts of my own. So I do it my way, which requires a bit of creativity, finesse, skipping and combining steps, closing off loops, and anticipating the algorithm’s zigzags, which keeps life interesting. But although it all seems to be going well, I sense it starting to go wrong.

An inkling. But I’ve been trained to notice it. The twitch of Lisa Beagleman’s eye. The way she’s answering quickly but not eagerly. As if she’s rushing through it before she can change her mind. That’s it. She’s on the verge of changing her mind. But I have to make this sale. She is changing her mind. The difference between eighty dollars and twenty-four hundred. She’s changed it.

Shit.

I’m still zeroing in on a number, ping-ponging between six or seven different possibilities. A baby is crying somewhere in the coffee shop. Keep it together. Down to four possibilities. Lisa Beagleman herself might not know it yet, but I know it: she doesn’t want this anymore. The crying baby belongs to this man I can see over her shoulder. It’s just him and the baby. Maybe he’s a single dad, trying to take a break at this coffee shop and his baby is freaking out. Down to three possibilities. The baby is a girl. A handful. Last calculation, simple, just multiplying two numbers. Always thought I’d rather have a daughter.

I have the answer.

Lisa Beagleman is trembling. I clear my throat. She doesn’t want to know. Well, make her want it. I see her eyes darting, trying to get out of it. I’m about to tell her exactly how much time she has to live. She’s backing out. Don’t let her. Afraid. The naked fear. What I used to see.

Lisa Beagleman opens her mouth but before she can say anything that would nullify the contract I say, “Lisa, you’re going to die in six years, eleven months, four days, and nine hours.”

—0—

Oh Jesus, I fucked up. Shouldn’t have forced it.

She breaks down crying. “I told you I didn’t want it,” she weeps, nearly screams, and it doesn’t matter that it’s not true, that she never explicitly told me she didn’t want it, but no, I messed up, it is my fault, because after all I could read it in her manner. Now she’s making a scene—this is why we used to do it in an office, not in public—and she’s wailing! Breaking down!

I’ve never misjudged so badly but I’m ashamed to admit, when her smug mask broke, my first thought was, at least here’s someone who feels it. And when most people cry, it screws up their face, makes them look abject, but for some people, like Lisa Beagleman now, there’s a hidden dignity that’s unlocked when they cry, her eyes no longer so verminous, so calculating, even though I can’t understand what she’s saying through her tears except, “And I’m never even going to see Mandy go to high school, to puh-puh-puh- puh-prom,” standard shit. When they’re spiraling they always latch onto some random life milestone that they just then realize they’ll never experience. The man with the baby comes over from the other table, “Is everything all right?” and oh Lordy, now super-dad is sizing me up, like we might have to “take this outside,” and I’m too stunned to do anything other than offer a handkerchief to Lisa Beagleman, but she swats it away and howls, “Six years.”

“Practically seven,” I say, stupidly.

“I told you I didn’t want it,” she weeps. From the way she’s interacting with super-dad as he comforts her and I sit there like a stone, it becomes apparent they know each other, that super-dad is “David,” that their kids go to preschool together, that “David” is stepping in as a protector. He turns to me and says, “It’s probably time you left.”

Oh hell no. “I need Mrs. Beagleman to sign this confirming that she’s received the information.”

“You can get her to sign it later, buddy.” Buddy! Now I’m “buddy.” David is hugging Lisa Beagleman now, comforting her. I’d judge her hysterics as over-the-top if I hadn’t witnessed the exact thing before, so many times—never on my watch, but when less adroit salesmen fail to stick the landing, amateurs who don’t have the balls or the backup to walk away when you’re supposed to walk away—well, this is why Martin McNiff does it over the phone, right? McNiff doesn’t care. Mandy and her puh-puh-puh-puh-prom . . . did you know McNiff has moved into the market for under-21? Used to be an unwritten rule you don’t do that, but it turns out the testing goes even quicker with babies and toddlers because there’s zero self-consciousness fogging up their assessment responses. Well, if you can look into the eyes of brand-new parents and inform them their child will die of cancer when they’re four years old (72.3%) or in a car crash when they’re twelve (23.8%), etc., and then have the transcendent balls to bill them for the pleasure, you’re welcome to it.

In any case, McNiff has no problem picking up the check. Neither do I, apparently.

I have the paper out, the pen out. Lisa Beagleman’s got to sign if I’m going to get my miserable twenty-four hundred dollars and I am not walking out of this shitshow without my twenty-four hundred dollars. Everyone is glaring at me, even the baristas. I’m the bad guy, I’m the scum of the earth. Well, you know what? I’ve got a signed contract. She asked for this. She went through the assessment. She paid her money. I kept up my end. Am I always going to be the good guy in life? No. Learned that ages ago.

“You’re still here?” says super-dad David. I don’t move. “Sign.”

—0—

Wet white flakes flying at my windshield. Slush world changed to snow world while I was inside. December in the suburbs of Chicago, where am I even? Schaumburg or Palatine or purgatory, swinging out of the parking lot, blasting down the avenue, onto the highway, like a criminal getaway minus the charm. Lugging the Books of the Dead out of the Starbucks, nobody asking “Can I give you a hand with that?”—everyone knew what had happened, they’d seen similar scenes before. But it had never happened to me. Lisa Beagleman screaming me out the door. Shouldn’t have told her. Too eager. Like a chump franchisee. Like some asshole who’d just earned his license, who rents his Books of the Dead by the week.

And to think I’d been one of the first ones.

It’s death-dark and I’m driving around a shaken-up snow globe. Two lights come blazing out of the blackness, zoom past, another idiot stupid enough to be driving in a slushy shrieking blizzard. But I had to get out of there. Not just out of the Starbucks. Out of the parking lot. Out of town. Out of that whole world. Lisa Beagleman and super-dad David, turning the crowd against me. Won’t be doing business in there again.

She’ll call headquarters. She’ll make a complaint.

Ron Wolper.

Oh, Christ.

But that’s what you wanted, wasn’t it, Wolper? For me to be more aggressive? To push that sale? Oh no, don’t blame Wolper, it’s you, you knew it was a dick move even while you were doing it, you didn’t listen to your own judgment. Because be honest: you would’ve held back, you wouldn’t have told her if you’d liked her. But from the minute you saw Lisa Beagleman you didn’t like her. She didn’t like you either. Natural enemies. Who would win. Well, I won. She’s the one crying. I got my percentage.

Dick, dick, dick.

This blizzard is something else. Dumb being out here. The flying white streaking by in the blackness swallowing up the car, like I’m blasting through hyperspace. Brutal wind. Car hard to handle, the wobbly way it takes the curves. Well, you’d said you wanted a white Christmas . . . You say that every year. Weaving, almost fishtailing. Careful what you ask for. Home still miles away, why in such a hurry to get there? Nobody’s waiting for you. Complain if there’s no snow in December it doesn’t feel like the holidays; complain if there is snow in December it’s too much to handle—digging your car out in the morning, hours of traffic—

I hit the skid. Fly off the road.

—0—

Acar crash doesn’t feel the way you think it’ll feel. Or it didn’t for me. Not enough time for panic, for freaking out, not enough time for your body to catch up to what’s happening, for

your brain to zap the right chemicals out to the right muscles— when I hit the skid and fly off the road, I am calm, I do everything correctly, I keep control as much as possible, try to minimize the damage, even as I think in a resigned way, This is it. Now I’m dead.

Crumpled in a snowy ditch. Car totaled. Then the rush comes, the useless adrenaline. All the emotion I should’ve felt, too late.

Dare To Know by James Kennedy will be released on 14 September.