Few TV writers’ names are as marquee-friendly as ‘Gene Roddenberry’. In that original Star Trek title sequence, his screen credit zooms in before even William Shatner’s. In 1985, he became the first ever TV writer to be awarded a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Ask any keen TV watcher who Gene Roddenberry is and you’ll get: “The creator of Star Trek.”

Yet Roddenberry’s relationship with Star Trek was a complicated one. He was deeply possessive of the show, but he was also – occasionally – resentful of it. And while Trekkers deified him, Paramount was less smitten, often preferring to keep him as far away from Star Trek as they could without alarming the fanbase.

Gene Roddenberry would have loved to have fathered another series that was adored as much as Star Trek, but another success always eluded him. Though it wasn’t for want of trying. His career is littered with television pilots that never took flight, with books that were never finished, with movies that never lived up to their potential.

So when everything else failed, he found himself, in the twilight of his life, back at the bosom of his most famous creation. However, much as he might have hated it, every newspaper report, when he died on 24 October 1991, referenced Star Trek in its headline.

Reading those obits, it’s brain-blowing how much Eugene Wesley Roddenberry packed into his 70 years on this Earth. Writers now, generally speaking, aren’t armed with the same real-life credentials as Roddenberry experienced. His wasn’t a moneyed, cloistered background, of private schools and Harvard and New Yorker internships. Majoring in police science at Los Angeles City College, Roddenberry joined the United States Army Air Corps when he was 20 and became a pilot for Pan-Am when he was 24, in 1945. Two years later, a plane he was piloting crash landed in the Syrian desert. Roddenberry dragged injured passengers from the burning plane and led the group to get help. In total, 14 people died in the crash.

Roddenberry quit Pan-Am in 1948, itching for a job in which he could flex his creative muscles. But with few writing jobs out there for a one-time pilot with two young kids, he applied for a job with the Los Angeles Police Department. After just over a year in the traffic division, he was transferred to the newspaper unit, where his responsibilities included penning press releases (writing at last!) and speeches for the Chief of Police. It was around this time that Roddenberry had his first professional brush with television, when his boss assigned him as technical adviser for a new police procedural series titled Mr District Attorney

Roddenberry soon proved so invaluable that he started penning scripts for the NBC show, which in turn led to writing gigs on the crime series Highway Patrol and on the political drama I Led Three Lives. By 1956, struggling to juggle his dual careers of policeman and writer, he resigned from the LAPD.

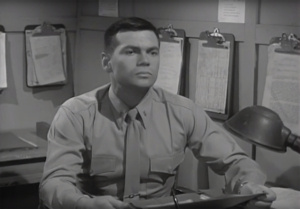

Roddenberry’s first job as a full-time TV scribe was on the long-forgotten anthology show The West Point Story, eventually penning a third of the series’ overall episodes. There were other shows too, all unremarkable in their own ways – the westerns Bat Masterson and Jefferson Drum, the seafaring adventure show Harbormaster, the crime drama Highway Patrol. All the time though, Roddenberry was beavering away on his own series pitches. Some made it to pilot – The Wild Blue, Police Story, 333 Montgomery (starring DeForest Kelley as a Perry Mason-styled big city lawyer), others never even got that far.

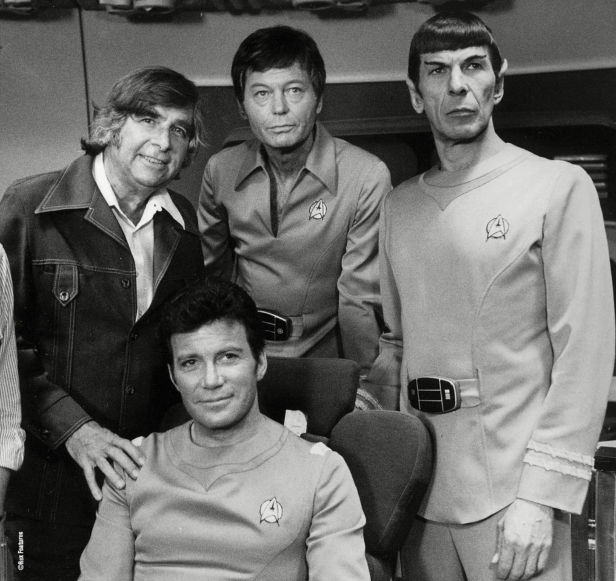

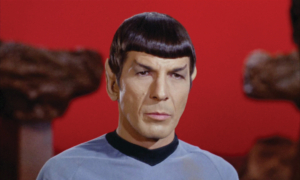

He finally hit upon a pitch that CBS wanted with The Lieutenant in 1963. It was on this show that he made many of the professional connections that would continue into his next created series, from producer Gene L. Coon and casting director Joe D’Agosta to actors Gary Lockwood, Leonard Nimoy, Walter Koenig Nichelle Nichols and Majel Barrett.

The Lieutenant had benefited from having the US Department of Defense as advisors, but they withdrew their support after Roddenberry, ever the provocateur, pressed ahead with an episode titled ‘To Kill A Man’, about racial prejudice in the Marine Corps. The Lieutenant’s days were numbered after that.

The Lieutenant was canned in 1964, and Roddenberry swiftly began work on the pitch that would, just a few years later, become Star Trek. In fact, that original treatment was a thrifty blend of various story ideas Roddenberry had been toying with over the years. One rejected pitch, from 1956, focused on the crew of a cruise ship. Another had an airship, peopled by a multiracial crew, travelling the world. The difference this time was that Roddenberry had given the pitch an attention-grabbing science fiction makeover.

Star Trek was never a ratings topper over its three years on television. In fact, it veered perilously close to cancellation at the end of its second year, only to be given a last-minute reprieve (although it was moved to the less hallowed slot of 10pm on Friday nights). Roddenberry, pissed off and burned out, stepped down from his day-to-day running of Star Trek after its second year. The show’s third and final season was overseen by the less visionary Fred Freiberger.

Star Trek was also never, at the time, a prized asset for Paramount. It took over 15 years, it’s said, for the series to become profitable (even in 1982 the series was $500,000 in the red) and the show had the stink of failure about it. Roddenberry felt that he was “perceived as the guy who made the show that was an expensive flop”. He later said of the years after Star Trek: “My dreams were going downhill because I could not get work after the original series was cancelled.”

Roddenberry had been aching to break into movies for as long as he had been writing. There were various near-scrapes, including an attempt to reboot the moribund Tarzan franchise, but, when that was downgraded to a TV movie, he bolted.

Roddenberry’s first big screen credit was to come with a tawdry sexploitation flick titled Pretty Maids All In A Row. It was directed by Roger Vadim, the Euro auteur who had introduced the world to Brigitte Bardot in And God Created Woman and helped make Jane Fonda a futuristic pin-up with Barbarella, but even his super-hip name attached to the movie couldn’t save it. Pretty Maids All In A Row bombed (although Quentin Tarantino once named it as one of his top 12 all-time movies), and Roddenberry’s dreams of big screen glory were dashed.

With little writing work on the horizon, Roddenberry began to fill his time guesting at science fiction conventions. If he couldn’t feel respected in the meeting rooms of the major studios and networks, at conventions he was lionised. Here he would screen episodes of Star Trek and begin painting a picture of himself as the man who kicked against the corporate pricks, the radical visionary who fought against a philistinstic and reactionary network.

He was still pitching to those networks however. His 1969 divorce had him paying $2,000 a month to his ex-wife and Roddenberry needed the bucks. One pitch, Genesis II, a joylessly solemn post-apocalyptic drama about a Buck Rogers-like character from the 20th century waking up in the 22nd, made it to pilot stage, but in the end CBS, looking for a more seemingly sure-fire ratings champ, opted for a Planet Of The Apes series.

Equally luckless was The Questor Tapes, which headlined Robert Foxworth as an android with an incomplete memory searching for his creator (so, a little bit Data, a little bit Star Trek: The Motion Picture). But Roddenberry found himself forever butting heads with Universal, who wanted numerous format changes. Unable to come to a compromise, Gene Roddenberry walked.

During this time, Roddenberry was still dining out on Star Trek, and, at the beginning of 1973, there seemed hope that Star Trek might return, only this time as animated series. The company Filmation beat out Hanna-Barbera for the cartoon rights, and although Roddenberry had no interest in running the show on a day-by-day basis, he corralled together most of the creative talent for the series’ 22-episode run, including TOS veterans DC Fontana, David Gerrold and Marc Daniels.

Still believing there was mileage in the Genesis II concept, Roddenberry pitched it again to rival network ABC, with a fresh monicker – Planet Earth – and a new leading man in the livelier John Saxon. But it wasn’t picked up. Neither was his next pilot, the occult detective drama Spectre. It seemed that unless that programme had ‘Star Trek’ in the title, none of the networks were interested.

The first rumbles of Star Trek’s second coming were felt in the mid-Seventies. The initial idea was for a new TV series, and indeed plans were being drawn up for a two-hour pilot, and a series of 13 episodes. But Star Wars’ barnstorming box office performance convinced Paramount that Star Trek was potentially more profitable as a big screen event. Before too long, Star Trek: Phase II, as it had become known, had become Star Trek: The Motion Picture.

STAR TREK and related marks and logos are trademarks of CBS Studios Inc. All Rights Reserved.)

Roddenberry was tasked with reworking writer David Livingstone’s Phase II pilot script, ‘In Thy Image’, for the multi-million dollar movie. In fact, The Motion Picture’s script would ping-pong between the two of them, with eventually even William Shatner and Leonard Nimoy having a crack. But unlike the television series, Roddenberry wasn’t the one in charge, and his objections to one scene cooked up by his leading man were effortlessly overruled.

Roddenberry was barely involved with the Star Trek movie sequels. His official title on Star Treks II-VI was ‘executive consultant’, which meant he would cast his eye over any script and would make notes for the director. But, crucially, the director wasn’t obliged to read them. Gene Roddenberry was a king in exile.

Which is why Star Trek: The Next Generation meant so much to him. In many ways, especially in those first few seasons, it’s the purest example of Roddenberry’s dreamily idealistic vision of Star Trek.

The initial brainwave for a rebooted series had come, in the summer of 1986, not from him though, but from Paramount. And Roddenberry had actually turned them down on their first offer, unimpressed with their initial plans for the series. But Paramount knew that any Star Trek series launched without the blessing of its original creator would be a damn hard sell, especially without the comforting presence of Shatner, Nimoy or Kelley.

So, with a bounteous pay packet (he was awarded a bonus of $1 million in addition to an ongoing salary to produce the series), Gene Roddenberry was once again the head honcho of a Star Trek TV series. His health, however, in 1986, was the worst it had ever been. His recreational drug use had ballooned in the fallow ‘executive consultant’ years and his drinking was so out of control he checked himself into a drying out clinic upon getting the Next Generation gig.

Although the main characters and the basic setup of The Next Generation have Roddenberry’s prints all over it, the reality is his grip on the series weakened considerably after that first season. Maurice Hurley was brought in as showrunner for the show’s second year, and, although Roddenberry was still being consulted (“you don’t know the difference between shields and deflectors!” he bellowed at Hurley during one meeting), his health was deteriorating fast.

A stroke in 1989 confined him to a wheelchair and his involvement in Season Three was virtually non-existent. Then, on 24 October 1991, he suffered a cardiac arrest and died, outside the offices of his doctor. Two weeks later, the Spock-starring Star Trek: The Next Generation episode ‘Unification’ aired with a on-air dedication to its late creator.

A year after his death, some of his ashes were flown in to space on the shuttle Columbia. Five years after that, on 21 April 1997, seven grams of his cremated remains were launched into Earth orbit aboard a Pegasus XL rocket. The rocket remained in orbit until 2002 when it disintegrated in the atmosphere.

All these years on, Gene Roddenberry’s name is still there, emblazoned over the credits of every episode of the Star Trek series, Discovery. It is a fitting tribute to a man whose stirringly bright-eyed vision of the future helped birth a culture-quake phenomenon, a writer who really did go where no writer had ever gone before.

Star Trek: The Motion Picture – Director’s Edition available on 4K UHD + Blu-ray now