If you had to describe Paul Verhoeven in just one word, ‘enthusiastic’ would be the perfect choice. Critics, however, have labelled him a closet fascist, a director with a taste for sex and violence and a penchant for making crass mass-market fiction. And with movies like Basic Instinct and Showgirls, you can see where some of the brickbats come from. Yet talk to the man himself and you realise he has great enthusiasm and passion for film. His movies are imbued with controversial, often-confrontational politics but a sense of humour is never too far behind.

We caught up with Verhoeven as he was travelling around the Netherlands to promote his latest movie, Black Book, a film about a Jewish woman who goes undercover for the Dutch Resistance during the Second World War. His excitement peaked, however, when we got him talking about his sci-fi flicks…

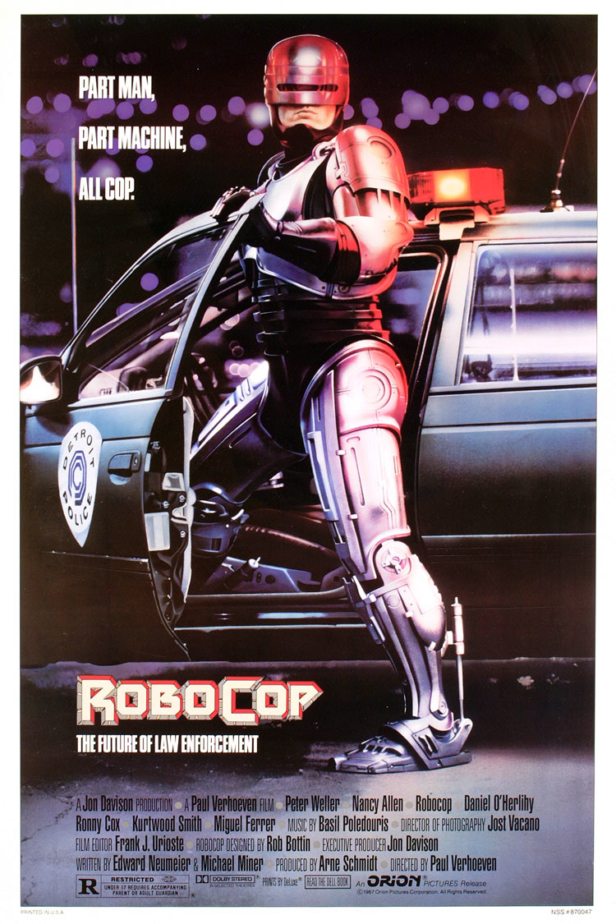

It’s well documented that before you made RoboCop, you weren’t a massive fan of science fiction. Why was this?

In the Netherlands, realism has always been a great art form and it was a key aspect of my work. Artists such as Rembrandt had a fondness for humble subjects and it’s engrained in Dutch culture. When I made my first movies, I was just keeping in line with that trend.

So was being asked to direct RoboCop a shock for you?

Definitely. RoboCop was so alien to me and I couldn’t get my head around this whole concept of the future of law enforcement. I’d received the script and my first thought was, “What the fuck is this?” I was straight on the phone to Barbara Boyle [senior vice president of worldwide production at Orion Pictures Corporation] and I told her I couldn’t do it. I just didn’t understand it at all.

You’ve said in the past that your wife influenced you to make the film. What happened?

I was on the beach in the south of France and my wife was reading the script. She turned to me and said I’d made a big mistake in casting it aside. She believed there was great irony in the film, which I would be able to handle well. She eventually persuaded me to take another look and when I did I realised there was material I could work with, that the film was deeper than I originally envisaged.

Did you think about bringing a sense of Dutch realism to the movie?

One of the reasons many European directors fail to make it in America is because they have felt they could do their own thing in Hollywood. I realised pretty quickly that if I was going to be a success in the States that I would just have to go with the flow. A friend advised me to do that, and it was the best advice I could have received. I had it in my mind that I would not try to make my own movie.

RoboCop appears to have an almost distant relationship with American culture. Why is this?

Perhaps I was naïve but when I arrived in America I was amazed. I was curious about the things that were shown on television and in the cinemas and, having not been in the US for that long, I was able to distance myself and look at American culture in an ironic way. I didn’t know the US audience and their tastes all that well so I could kind of view it from afar. I believe I succeeded because of the distance I had to American culture at that time.

Is that why the Media Breaks were used to great effect in explaining the worsening social conditions in Detroit?

I used those Media Breaks to tell more of the story, pulling them away from the script and giving them a sense of social collapse. I had an alienation to American culture in a way and these Media Breaks also let me convey my highly amazed look at US television.

Did the fact that you come from a European background prove a problem while you were making RoboCop?

At times it would. But I had good scriptwriters in Edward Neumeier and Michael Miner, a great producer and a good special effects team. I didn’t know anything at all about special effects so it was invaluable to have such expertise to hand. And with all of these people next to me, I was protected against Europeanism. They would warn me at times that no one would talk in this way or that people just don’t act like that and it helped to keep things on track. I believe RoboCop is the best American movie I ever made and it’s thanks to these guys.

Which movies inspired you during the making of RoboCop?

Terminator. I studied that film immensely and I believe Cameron to be a fine film director. The Terminator was very innovative, a real classic. Yet I recall talking to Arnold Schwarzenegger about that film and he was really upset. He felt it had not been promoted properly and was being seen as some ‘fucking b-movie’. Of course, people view it as a wonderful film now. I feel RoboCop had greater sophistication but I also feel Arnold did a great job and I was keen to work with him on a future project.

Of course, that came with Total Recall.

It did. I took the same approach with Total Recall as I did with RoboCop. I had writers on the set at all times, for instance. But Arnold had great input into that movie too. He was very passionate about it and we worked extremely well together. There were times when he would be unhappy about certain decisions that the studio was making with Total Recall, little things like cutting or changing scenes and things like that. Arnold would stand up and demand they be left alone, threatening to leave if they weren’t. Having that enthusiasm and support around was brilliant.

Sharon Stone was also in Total Recall and, famously, went on to star in Basic Instinct. She frequently says she was upset by ‘that’ scene…

After Sharon had starred in Total Recall, I just knew I wanted her to appear in Basic Instinct. She was the perfect actress and having her and Michael Douglas together worked so well. The scene in which she uncrossed her legs did upset her but she was fully aware it was being shot and had given permission.

Shortly after Basic Instinct, you directed Showgirls – a film for which you accepted a Golden Raspberry for worst director – then went on to direct Starship Troopers. And people began to call you a closet fascist.

Those accusations amazed me. There were these people accusing me of being a Neo Nazi! Starship Troopers was a personal film for me but it was my commentary on American foreign policy not fascism. I also took a lot of what I witnessed as a child in the Second World War in Rotterdam and translated that to the big screen. Where that battle was against the Germans, Starship Troopers had spaceships in battle against bugs.

Starship Troopers also displayed your trademark violence, gore, nudity and bad language. Do you find it necessary?

If you look at a film like Starship Troopers, we have these bugs which stab, cut and kill. It’s going to be difficult to make a film like that without some violence and gore. Take that out and you lessen the film’s impact. It would change the movie completely and I feel that about all of the movies I’ve made.

Are there any films you regret – Hollow Man, for instance?

To be honest Hollow Man felt hollow and I was starting to get fed up with the situation in the US. I wanted to do something for me and I was beginning to feel unable to make those sort of personal films. With Hollow Man, I felt I was trying to do this US project but not doing it very well and I just needed a break. It was frustrating at times: I had an idea of creating a film about Victoria Woodhull, a 19th century feminist who had run for the American presidency, but the US studios were not willing to make such a project.

So is that why you decided to leave the United States after you filmed Hollow Man?

Yes. In 2003, I began to work on Black Book with writers in Europe. The difference here is that money is not as easily available so we had to wait until the funds had been generated. The film was important to me though. After doing it, I felt myself again, that I was doing something that I cared about.

So what are you working on at the moment?

I’m writing a book about Jesus. I’m not a Christian but I became fascinated by Jesus and have been studying his life since I moved to the US. I’m attempting to look at the gospels, at what Jesus said and did and work out what is authentic. It’s going to look at Jesus as a man. You’ve said in the past that Murphy in RoboCop was a metaphor for Christ. Was this deliberate? Yes it was. I saw an opportunity for these metaphors in the film and so I just had to grab hold of them and fill them in. For me, there is a comparison between Murphy’s death and resurrection as a RoboCop, with Christ and Christianity’s teaching of a resurrection. With Murphy, his memories had been lost but he began to recover them and learn of his past life.

It’s clear you have a lot of affection for Murphy…

He was a complex character. At the end of RoboCop when Dick Jones, the senior vice president of OCP threatens to shoot the Old Man, RoboCop has his Directive Four overruled when the Old Man fires Jones. This allows RoboCop to shoot Jones and the Old Man says to him: “Nice shooting, son. What’s your name?” I recall a movie screening I held in New York where, at this point, the whole audience shouted “Murphy” before RoboCop himself answered with that same word. I felt so proud and happy – the audience realised what we were trying to do and the depth of the character we were trying to create. People saw Murphy inside that RoboCop suit.

Will you make a RoboCop sequel?

Ed Neumeier and I have spoken about it in the past but nothing firm has come of it. I think it’s unlikely to happen.

Are you just going to concentrate on non-English language films? Will we see you direct a non-English language science-fiction movie?

It’s difficult to release a Dutch/German movie in the US, UK, France, Spain… For it to do well really depends on the tricks pulled by the distributors. In that sense, it limits me especially in terms of budget. And science-fiction films are expensive. But the fact that Black Book, for instance, is being seen all over the world is an enormous step forward in comparison to earlier movies I made in the Netherlands, which were moderately successful worldwide. You lose about 90 per cent of the audience when you make a foreign film. There’s no denying that US films have had advantage for the last 100 years.