War Without End – Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Fantasy

By Gail Z. Martin

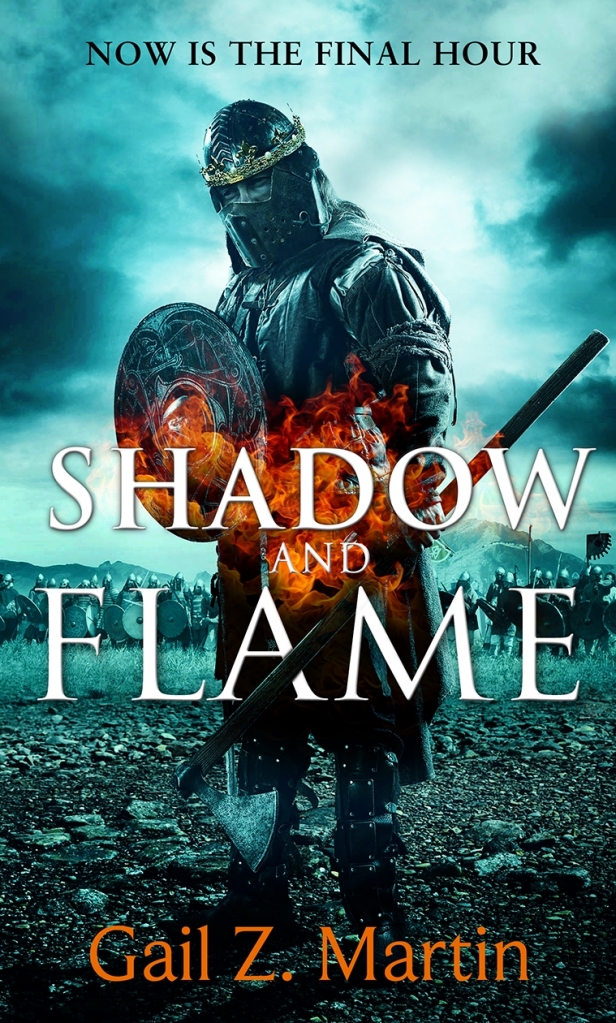

I’m an epic fantasy author, so I write a lot about war. My main characters are soldiers – whether by intent or fate – and they fight a lot of battles. The Ascendant Kingdoms Saga, my current series (Shadow and Flame is the newest and final book), has a post-apocalyptic medieval setting. A disastrous, protracted war between two powerful kingdoms ends in a fatal magical strike that causes devastation in both kingdoms. The Cataclysm and the Great Fire, as the events come to be called, result in the decimation of an entire generation of young men, destruction of critical infrastructure and loss of leadership – with dislocation, famine, and disease following.

Pretty grim stuff, yet all of it with historical precedence. Which has led me, over the years, to spend a lot of time reading books about war – scholarly recaps, historians’ attempts to place conflicts in a broader context, and the memoirs of soldiers themselves. What strikes me in all of those retellings is that trauma is not reserved simply for soldiers or for the fairly small percentage of the population unlucky enough to be in a war zone. My take-away is that what we now call Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder is much farther-reaching in scope than we realize (or may want to admit) and that every war fought continues to visit post-traumatic repercussions long after the peace treaty is signed.

I find it curious that we’ve only really been talking about ‘shell shock’ and ‘battle fatigue’ for roughly one hundred years, though wars have raged since the beginning of recorded history. We have a profound desire to believe that when the swords are sheathed and the guns are put away we can all go back to ‘normal’. Soldiers face huge cultural pressure to pop back into work, family and community as if they were just off on a protracted holiday. Countries that were bitter enemies often become fast allies within a few years or decades. Civilians whose homes, livelihoods, families and countryside were obliterated are expected to move on as if nothing happened. We want so hard to believe that all the awfulness suddenly goes away, like flicking a switch. We want that so badly, we remain stubbornly deaf and blind to the ramifications, even when they’re glaring.

Let’s think about the cumulative damage. Soldiers who die in battle leave behind them mothers, fathers, siblings, spouses, children, friends and neighbors who will never be the same because of that untimely loss. On top of the deep psychological scars from the death of a loved one, add in the loss of income and the loss of someone on whom a family depended for economic security. Such a loss can easily send a family into catastrophic and long-lasting economic and emotional turmoil, impacting the ability to work, family relationships and behavior in the community. Wounded and maimed soldiers return but they carry visible evidence of the war in their bodies, and those injuries will have an economic effect on their families as well. Even soldiers who return without diagnosable PTSD have witnessed – and possibly committed – horrors that civilians can’t understand. They are not the same people they were when they left. They will not interact with the people around them in the same way as they did before the trauma, and that will affect them and everyone around them.

Soldiers who return with PTSD face a host of additional problems that play out and affect the larger community and society. Children who grow up around battle-traumatized soldiers are themselves traumatized by the soldier’s emotional withdrawal or angry outbursts, by parents who fight and marriages that break up. These problems radiate beyond the nuclear family to the extended family, friends, neighbors and community because they create impacts and deficits that spread out like ripples from a stone thrown in a pond.

Only it doesn’t just affect the families and communities of soldiers or the civilians in war zones. I’ll argue that entire countries are traumatized by wars, both the victors and the vanquished, in ways we don’t want to acknowledge. Certainly the outcome of war influences policy. Wars have to be paid for, infrastructure must be rebuilt, and so other programs like education and medical care and aid to the most vulnerable in society is often cut, directly impacting the course of the future. Generals are often said to be ‘fighting the last war’ in the decisions made the next time conflict nears. Desperate to avoid making the same mistakes twice, they fail to respond to the current conditions and often precipitate needlessly tragic outcomes.

What does this have to do with fiction? Plenty. When we as authors create fictional wars and set made-up kingdoms against each other, it’s tempting to move on to the next thing when the treaty is signed. Yet to do so, I believe, is unrealistic at best and damaging at worst. Readers learn through fiction. When we uphold the notion that war ends when the shooting stops, we miss a chance to make our readers think about the true cost of conflict and the long-term damage that continues long past armistice. We play into the convenient belief that war affects only the combatants, and we fail to bear witness to the powerful undercurrent of unaddressed trauma that manipulates personal, regional and societal values, choices, decisions, and policies like the hand of an invisible puppeteer. In other words, writing about war without acknowledging the long-term effect of trauma is simplistic and inaccurate and robs our stories of a deeper meaning and richness.

Yeah, I know. Them’s fightin’ words. But I’m sticking to my guns on this one.

Shadow and Flame, Book Four in the Ascendant Kingdoms Saga from Orbit Books is available in stores and online in trade paperback, ebook and audiobook now.